Bones

(Author of "Castaway," "The Planet That Time Forgot, etc.)

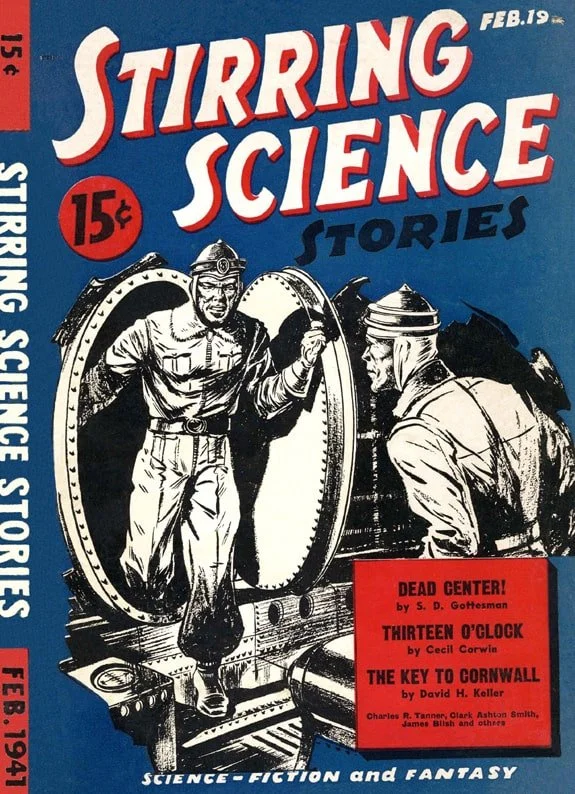

Originally appearing in Stirring Science Stories, February 1941.

Where there once was life, new life may arise . . . but what of that which was never alive?

The Museum of Natural Sciences was not very far from where he was staying, so Severus found himself striding briskly through the dark, winding streets that night. He had come to Boston on a visit, renewed acquaintances with learned men with whom he had exchanged knowledge in years past; thus, the letter he had received in this morning's mail inviting him to a private demonstration this night.

It was not a pleasant walk; already, he was beginning to regret not having taken some other means of transportation. The buildings were old and loomed darkly over the narrow streets. Lights were few; for the most part, they came from flickering, dust-encrusted lamp posts of last century's design. Giant moths and other nocturnal insects fluttered over their surfaces, added their moving shadows to the air of desolation which hung about these ways.

The moon was behind clouds that had streaked across the autumn skies all day and now blocked out the stars. The night about him was warm with that touch of unexpected chill which comes in autumn; Severus shuddered more than once as a wandering breeze slithered across his face unexpectedly around some dreary corner. He increased his pace, looked more suspiciously about him.

Boston, the oldest section of the city. Antique brick buildings dating back to the revolution, some much farther. Dwelling places of the best families of two centuries ago. Now steadily advancing progress and life had left them derelict on deserted shores. Old, three or four-story structures, narrow tottering dirty red-bricked houses with yawning black windows that now looked out through filth-encrusted panes upon streets and by-ways that served to shelter only the poorest and most alien section of the city's people. Forgotten, the district imparted its despair and overhanging doom to the man who walked its ways that night.

Half conquered by the smell of the antique houses, the subtle vibrations of past generations still pervading his spirit, Severus came at last out of the narrow streets into the open square where stood the Museum.

The change surprised him. Here all was open. The dark, cloud-streaked sky loomed down overhead with a closeness that appalled him for a moment. The white marble facade of the structure glistened oddly in his view. It stood out, the cleanliness of it, as something exceedingly out of place, as something too new, too recent to have any right here. Its Neo-Grecian designs were horribly modern and crude for the Eighteenth Century blocks that surrounded it.

He walked swiftly across the open square, up the wide stone steps to the entrance of the building. He quickly thrust open the small side door and hurried through as if to escape the thoughts of forgotten streets outside.

How futile such hopes in a museum! He realized that the instant, the door was closed. He stood in a dark hall, lit dimly by one bulb above the entrance, another at the opposite end of the main passage. And at once, his nostrils were assailed by the inescapable odor of all such institutions—age!

The musty air rushed over his body, took him into its folds. The silence assailed his ears with a suddenness that all but took his breath away. He looked about, trying to catch his bearings. Then he ventured a step, walked rapidly across the large chamber, down a wide corridor opening off it. Not a glance did he cast from side to side. The looming shadows of indescribable things were enough for him. His imagination supplied the rest. Unavoidable glimpses of shadowy sarcophagi and grotesquely carven idols sent great cold chills thrilling down his spine, stirring up his heart,

Up a narrow staircase, a turn to the right, at last, he was at the room set aside for the night's demonstration; he stood a moment trying to catch his breath and regain composure. Then he pushed the door open, stepped inside.

A bare room with scarcely any furnishings. About seven or eight other men were there. In low tones, they greeted him, drew him over to their circle. All were standing; there were no chairs in the room. A couple of small instrument-racks and the principal object were all.

The room, dominated by a long, low table, rested a six-foot bundle of dull gray cloth like a giant cocoon. Severus stared at it a moment, then recognized it as an Egyptian mummy removed from its coffin case. It obviously awaited unwinding.

So this was what he'd been invited to, he thought, wishing he hadn't been so friendly to the Egyptologists attached to this particular Museum.

Glancing around, Severus took note of the others present. He was surprised to recognize one as a Medical Doctor highly esteemed at a city hospital. The doctor indeed seemed to be one of the active participants in what was about to occur, for he wore a white smock indicating action.

Bantling, the Egyptologist, held up a hand for silence.

"Most of you know what is about to take place tonight; therefore, I will merely outline it for your convenience and for the one or two who know nothing about it." He nodded to Severus and smiled.

"This object, as you have all surmised, is an Egyptian mummy. But it is, we hope, different from all other such mummies previously examined.

"According to our thorough translation of the hieroglyphics of the sarcophagus whence this body came, this marks an attempt of the priesthood of the IVth Dynasty to send one of their numbers alive into the lands to come. The unique part of it, and that which occupies us tonight, is that this priest did not die, nor was his body in any way mutilated. Instead, according to the inscriptions, he was fed and bathed in certain compounds that would indefinitely suspend his body cells' actions; he was then put to sleep and prepared for a slumber very much like death, yet not an actual end to life. He could remain for years in this state yet still be re-awakened to walk again, a living man.

"In brief, and using modern terminology, these people of what we call ancient times claim to have solved the secret of suspended animation. Whether or not they did is for us now to determine."

Severus felt himself grow cold as this knowledge penetrated his being. The past had indeed reached out to the present. He would witness this night the end of an experiment that started thousands of years before. Perhaps he would yet speak to and hear talk about an inhabitant of this lost age. Egypt, buried these hundreds of centuries, Egypt aged beyond belief—yet, a man of that time-lost empire lay here in this very room, in the North American city of Boston.

"3700 B. C." he heard someone remark in answer to an unheard question.

Severus raised his eyes from the object on the table, let his gaze fall upon the window and what was revealed through it. Some clouds had cleared away, and the cold, bright stars shone through. Far-off flickering spots of light that must indeed have shone upon Ancient Egypt as coldly. The very light just passing through his cornea may have originated in the time when this thing upon the table was about to be plunged into Life-in-Death.

Far off, the dull clanging of a church bell drifted into the room.

"Buck up, old man." A hand patted Severus' shoulder as an acquaintance came over to him. "It isn't as bad as it looks. Why that fellow will be as strong and hearty as any of us before the night is out, you'll think he's just a new immigrant."

Bantling and an assistant were even now engaged in unwrapping the mummy. Rolls and rolls of old, crumbling cloth were carefully being unwound from the figure on the table. Dust of death and ages now filled the air. Several coughs were heard; the door was opened on the dark passage outside to change the air.

A gasp as at last the windings fell away. The body now lay entirely uncovered. Quickly, quietly, the wrappings were gathered together and piled in a receptacle while all crowded about to observe the Egyptian.

All in all, it was in a fine state of preservation. The skin was not brownish; it had not hardened. The arms and legs were still movable, had never stiffened in rigor mortis. Bantling seemed much pleased.

With horror, Severus noted the several grayish-blue patches on parts of the face and body which he recognized without asking as a kind of mold.

Dr. Zweig, the physician, bent over and carefully scraped off the fungoid growths. They left nasty reddish pitted scars in the body that made Severus feel sick. He wanted to rush out of the room, out of the building into the clean night air. But the fascination of the horrible kept his glance fixed in hypnosis on the gruesome object before him.

"We are ready." Dr. Zweig said in a low voice,

They began to bathe the body with a sharp-smelling antiseptic, taking off all remaining traces of the preservatives used.

"Remarkable how perfect this thing is," breathed the physician, "Remarkable!"

Now, at last, the way was open for the work of revival. Large electric pads were brought out, laid all over the body, face, and legs. The current was switched into them; the body surface was slowly brought up to normal warmth.

Then arteries and veins were opened, tubes clamped to them running from apparatus under the table; Severus understood that warm artificial blood was being pumped into the body to warm up the internal organs and open up the flow of blood again.

Shortly, Dr. Zweig announced himself, ready to attempt the final work toward bringing the now pliant, vibrant corpse to life. Already the body seemed like that of a living man, the flush of red tinging its skin and cheeks. Severus was in a cold sweat.

"Blood flows again through his veins and arteries," whispered the Egyptologist. "It is time to turn off the mechanical heart and attempt to revive his own."

A needle was plunged into the chest, and a substance injected into the body's dormant, thousands-year-old cardiac apparatus. Adrenalin, Severus assumed.

Over the mouth and nostrils of the former mummy, a bellows was placed, air forced into the lungs at regular periods. For a while, there was no result. Severus began fervently to hope that there would be no result. The air was supercharged with tension, horror mixed with scientific zeal. Through the chamber, the wheeze of the bellows was the only sound.

"Look!"

Someone cried out the word, electrifying all in the room of resurrection. A hand pointed shakily at the chest of the thing on the table. There was more action now; the chest rose and fell more vigorously. The doctor quietly reached over, pulled away from the face mask, and stopped the pumps.

And the chest of the Egyptian still moved. Up and down in a ghastly rhythm of its own. Now to their ears became noticeable an odd sound, a rattling soft wheezing sound as of air being sucked in and out of a sleeping man.

"He breathes." The doctor reached out and laid a finger on the body's wrist. "The heart beats."

"He lives again!"

Their eyes stared at what had been done. There, on the table, lay a man, a light brown-skinned, sharp Semitic-featured man, appearing to be in early middle age. He lay there as one quietly asleep.

"Who will waken him?" whispered Severus above the pounding of his heart.

"He will awaken soon," was the answer. "He will rise and walk as if nothing had happened."

Severus shook his head disbelievingly. Then—

The Egyptian moved. His hand shook slightly; the eyes opened with a jerk.

Spellbound, they stood, the eyes of the Americans fixed upon the eyes of the Ancient. In shocked silence, they watched one another.

The Egyptian sat up slowly, as if painfully. His features moved not a bit; his body moved slowly and jerkily.

The Ancient's eyes roved over the assembly. They caught Severus full in the face. For an instant, they gazed at one another, the Vermont man looking into pain-swept ages, into grim depths of agony and sorrow, into the Aeons of old Past Time itself.

The Egyptian suddenly wrinkled up his features, swept up an arm, and opened his mouth to speak.

And Severus fled from the room in frightful terror, the others closely following. Behind them rang out a terrible, hoarse bellow, cut off by a gurgling they barely heard.

The entire company, to a man, fought each other like terrified animals, each struggling to be the first out of that Museum, out the doors into the black streets and away.

There are parts of the human body that, never having been alive, cannot be preserved in suspended life. They are the bones, the teeth—strong in death but unable to defy the crushing millennia.

And when the Egyptian had moved his body and opened his mouth to speak, his face had fallen in like termite-infested wood, the splinters of fragile, age-crumbled bones tearing through the flesh. His whole body had shaken and, with the swing of the arm, smashed itself into a shapeless mass of heaving flesh and blood through which projected innumerable jagged fragments of dark gray, pitted bones.

END