CLAIMED BY THE DEAD

By John Tracey

Originally published in Horror Stories, January 1935

Interior artwork by Amos Sewell

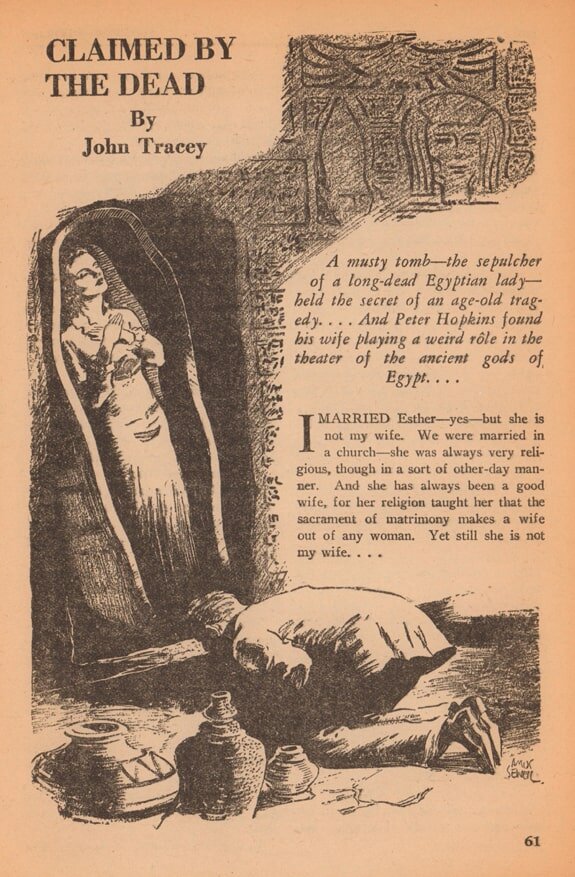

A musty tomb—the sepulcher of a long-dead Egyptian lady—held the secret of an age-old tragedy.... And Peter Hopkins found his wife playing a weird role in the theater of the ancient gods of Egypt....

I MARRIED Esther—yes—but she is not my wife. We were married in a church—she was always very religious, though in a sort of other-day manner. And she has always been a good wife, for her religion taught her that the sacrament of matrimony makes a wife out of any woman. Yet still she is not my wife....

I suppose she never was, really.... She was a strange creature of moods from the first—gay and charming when she played the hostess, but at other times often quiet and inscrutable, seemingly absorbed in her own strange thoughts and dreams. Yet the mystery of her, that suited so well her dark queenly beauty, made me love her the more. Had I known then her secret, perhaps I might have saved her. Now that I know it, it is too late....

Even before I knew, it did not seem strange to me that Esther had never shared my one great enthusiasm—my in satiable interest in Egypt and Egyptian lore. After all, I had lived there when a child. Ever since then it had fascinated me. I had studied at every opportunity the weird history of that strange civilization now lost in the darkness of the centuries. Always, I had wanted to go back, had worked constantly for an appointment there.

Then at last the appointment came. I was to be transferred to the Colonial Office at Cairo! I could hardly contain myself for my elation. I must tell Esther at once.

I stopped only long enough to purchase from a bookshop in Piccadilly all the volumes it possessed of Egyptian lore. I loaded these into a cab and dashed home.

I burst open the door. "Esther! Esther!" I called.

I dashed upstairs. She was in the drawing-room,

“Esther!" I cried. "What do you think? My appointment—"

She seemed to stiffen. “Your appointment to Egypt!"

I did not realize then that her words were edged with fear.

"Yes," I said. “Isn't it splendid?”

She rose suddenly from her chair. Her pale face was a mask of terror! “No! No, Peter! Not—"

She broke off abruptly, seemed to calm herself with an effort. "Of course," she said. “It is splendid. I knew we—I knew you would get the post.... I'll start to pack at once."

And without another word she walked out of the room, leaving me staring after her, dumbfounded.

WE ARRIVED at Cairo before the cocks had ceased to crow, in the clear coolness of an Egyptian morning a morning such as you will find nowhere else on earth. We sped behind a fezzed chauffeur through the Arab quarter to Shepheard's Hotel. As we walked up the broad steps of the terrace, a huge, affable—seeming man elbowed his way up to us.

"Mr. Hopkins," he said rather than asked, "I've been expecting you. I am Franz Boehler. Your father was a great friend of mine in the old days of Egypt ... so we shall be great friends, too."

I had known Boehler only by reputation, and I was immensely pleased at his cordial greeting. A colossus of body and brain, he was the man who controlled the government of Egypt and owned at least half of it.

We shook hands warmly. I introduced him to Esther. In the midst of acknowledging the introduction he stopped short. "Why.... why...." Then he smiled, greeted Esther cordially.

"Have you met my wife before?” I asked in surprise.

"No, no," Boehler hastily assured me. "Only a—a resemblance. It startled me a bit. But let us refresh ourselves.”

We sat down at one of the tables on the broad terrace. Soon we were sipping a cooling drink, chatting pleasantly. Yet Boehler now seemed preoccupied. His easy manner of moments before was gone.

Finally he said, rather abruptly in view of what had preceded it, "I have a tomb out in the desert which I think might interest you. I discovered it myself and I'm very proud of it. The workmanship of the interior is exquisite. It is the tomb of an unknown young Egyptian noblewoman of the Rameses era. In the burial chamber there is a very fine low relief wall-covering. It bears a most remarkable—" He hesitated, glanced queerly at Esther, then seemed to come to some quick determination. “Mr. Hopkins," he said, "would you and your wife care to see the tomb, sometime in the near future?"

I was on the verge of answering in the affirmative; but I had no chance.

"I should like to go," Esther said abruptly.

I started; so did Boehler. For her words had seemed a command rather than a statement....

ENGROSSED in my new duties, it was some days before I was able to give thought again to Boehler's tomb. I suppose it was always in the back of my mind; even so, it seemed rather odd, afterward, that the subject should have come up in my talk with Rachin Mahmoud.

I had met Mahmoud at my office as a result of a confidential government mission which came before me. He was a well-groomed, handsome young Egyptian, swarthier even than most of his people. We lunched together, and I found him a pleasant conversationalist. The talk turned to Egyptian antiques.

“I understand," said Mahmoud after a bit, "that Franz Boehler is taking you to see the tomb he discovered."

I started a trifle. How did he know? "Yes, indeed," I assured him then. "He's driving my wife and me out tomorrow."

"I'm extremely anxious to see it my self,” Mahmoud said. "Do you think you could arrange for me to join you?”

"Certainly. I'm sure Boehler wouldn't object. Meet us on the terrace of Shepheard's tomorrow at eleven. I'll have arranged it for you...."

At precisely eleven o'clock next day, Rachin Mahmoud mounted the steps of the hotel terrace to where we sat. He bowed low to my introductions, his hand on his heart in the Egyptian fashion.

Boehler, on the other hand, was not his usual affable self. He started visibly as he looked at Mahmoud. "Amazing!" he said, without seeming to realize he had spoken.

But it was Esther who alarmed me most. She acknowledged the introduction with a strange half-smile.

"I knew you would come," she said to Mahmoud.

Mahmoud, despite his suave mask of politeness, showed a trace of surprise. Boehler stepped quickly into the breech with some good-humored comment. I had no opportunity to question Esther's strange conduct.

We hurried to Boehler's waiting car, as if trying to put behind us the tenseness of the preceding moment. As the car whizzed through the cluttered streets of Cairo, scattering the yelling, selling Arabs to right and left, Esther remained perfectly silent, staring straight ahead as if lost in another world. She did not look again at Mahmoud. The Egyptian's eyes, however, seemed to be focused intently upon her. And in them there burned a peculiar light—a half-puzzled light, as if he knew an answer, yet could not quite name it.

As we passed the Pyramids and speed ed out through the desert, Boehler, on the other hand, seemed to expand with affability and good humor. Apparently he took no notice of the fact that I, of all his company, was the only one making any attempt to talk with him. Yet, tense as I was, I soon came to feel that even his

affability was but a mask for something else—that beneath it he, too, was strained and nervous, as if in expectation of some momentous happening about to occur.

We drove for an hour along the desert camel trail. Then the ground became more rolling. At last we wound up a long, somewhat rocky hill.

We were approaching the tomb. Now Boehler was obviously excited. His keen eyes snapped in anticipation.

"I always feel intensely moved,” he said, "when approaching my little tomb."

His enthusiasm was contagious; we all in some measure felt it. Esther, for the first time that day, showed signs of interest. Her eyes sparkled; her nose quivered as if having caught a familiar scent.

My excitement was of a different order. I was frightened. I felt, without knowing why, as if a climax were approaching; as if some dreadful event was about to bring to an end the strangeness of these past few weeks.

The tomb was hardly visible above ground, as the car came to a stop before it. An iron cage, built by Boehler against robbers, enclosed a short flight of steps that led down to a doorway hewn from solid rock. A huge rock slab, which once had sealed the doorway, now stood just at one side.

Boehler and his chauffeur busied them selves with arranging an extension light, by means of a light bulb with a long cord, attached to the car. Then, with the bulb in his hand, the big man unlocked the door to the iron cage.

"Mind the steps down," he said. “They're not any too regular." His voice sounded strange in the hush which had fallen over us. He helped Esther down the stairway to the door.

I sniffed the air. A musty, cloying odor of things long dead came up to me from the tomb—an odor as of an ancient drug.

What happened then seems confused to me now. I did not realize until after ward that Esther, strangely, had pushed on ahead of Boehler, with Mahmoud following close behind. Then, just as we had gotten well inside the passage, darkness descended upon us! Boehler, in his haste to follow after the two. had somehow caught the light-cord and pulled it loose from the socket.

The darkness seemed absolute, menacing. We stopped short. “I say, Henry, fix the light—quickly!" Boehler called to his chauffeur. His voice held a note that was almost fear.

In a moment there was light around us once again. It shone on finely—worked, beautifully-colored pictures depicting scenes of the time of Rameses Second. All along the walls on either side these paintings marched, forward toward the unknown end.

But throughout the length of the passageway, there was no sign of Esther or Mahmoud! The tomb had swallowed them!

A TERROR I could not name seemed to be driving me onward as Boehler and I raced down the echoing passage way. On either side, the light made flickering, living things of those weird wall decorations. I did not pause to look at them, and yet I saw them. And in a flash I seemed to fathom the depths of the old Egyptian soul, and find an answer there to all things. Those marching figures led ever onward, an irrevocable road of destiny—and their destiny was doom!

I do not suppose the length of the passageway was fifty yards; yet it seemed an eternity before we drew up, panting, at the doorway to the burial chamber. Here too, a huge slab of stone had been set aside to open the way. Boehler's light flashed inside and I gasped aloud.

For the muted rays of light shone on a niche in the far wall of the chamber. In that niche, stiffly poised and in the scant costume of an ancient noblewoman, I saw the form that bore the features of my wife! And in a niche beside her, in like costume, was Rachin Mahmoud! The features of both were stiff, immobile as stone....

Then my pent-up breath escaped in a long sigh, half-relieved. For what I had seen was actually two low-relief carvings on the wall of the chamber—but carvings, centuries old, that bore the exact features of Esther and Mahmoud!

As I looked on, astounded, a strange sound came to my ears and an eerie chill swept over me. The sound was a chant in an unknown, ancient—seeming tongue—a weird, unnatural song that sent shivers along my spine.

I turned to the sound. Boehler's light had shifted. What I saw now in the dimness left me stock still, staring.

In single file, at the far end of the chamber, three figures walked. They walked toward a doorway that opened in the wall, and the two in front went stiffly and with unseeing eyes, as if in a trance—Esther and Mahmoud!

But the one who directed them, who ordered them forward with chant and pointing finger, was the most fearsome of all. He was an old man, incredibly wrinkled and aged. It seemed that he might be countless centuries old and the robes that flapped about him were no denial of that seeming. Black as night and of a strange material, their blackness was interspersed with stars and moons and weird signs of the zodiac.

His costume was, in fact, that of a priest of Thoth, the hawk-faced God of the Dead, of the time of Rameses' reign!

Already now Esther, with Mahmoud close behind her, had passed through the doorway that led into blackness. With my heart beating madly in fear for her,

I came out from the spell that held me and started forward. But I stopped short.

The thing that stopped me was no spoken word—it was but a look that the old priest gave me. Only briefly, out of darkness, did his eyes flash toward me as I moved; but in that moment I saw mirrored there an ancient hatred and a malevolence so fearful that it chilled the very marrow of my bones!

While I stood, unmoving, he reached the doorway. Already the others had passed through. Now he turned again and spoke. I am sure he spoke in the language I did not know, yet I understood him.

"What belongs to the dead must come back to the dead," he said in deep, monotonous rhythm. “Thoth of the tomb has claimed his own."

There was a grating sound. Before my eyes a heavy door clanged shut. Where I had seen Mahmoud and the priest and Esther, was now only a hewn wall with no opening!

I think I went a little mad then. I rushed to the wall; I clawed at the rough stone where the door had been until blood streamed down my hands from the torn nails.

"Good God in Heaven!" I heard Boehler say. Then he was beside me, pawing the wall as frantically as I, though with more of a calm purposefulness. But where the door had been was only smooth stone, that seemed not to have been disturbed for centuries....

We stopped at last, exhausted. We looked into each other's eyes, searching for a faint shred of hope. I suppose Boehler must have seen the madness in mine, for he tried to calm me with well chosen words.

“This won't do it, old fellow," he said. "But there's a way. If I can—"

His words stopped abruptly at a sound.

It came from behind us, toward the entrance. We whirled.

The great stone that had stood beside the door was moving into the aperture as if hands had shoved it. We were being sealed into the tomb!

It was not quite shut. We rushed for ward together. Perhaps there was yet time.

And just as we reached that narrow aperture, Boehler shoved me roughly aside! Taken completely by surprise, I sprawled on the stone floor as he slid through. As I scrambled to my feet, the last crack vanished. The stone slid tightly into place.

With that, the light went out. I was alone in the darkness of the tomb. Alone—and buried alive!

I KNOW that then, for a little time, I was thoroughly insane. I pounded the stone walls with my bare fists; I screamed and shouted gibberish. And at last, exhausted, I sank to the floor....

Slowly, then, I forced myself by sheer power of will back to sanity. This mad effort, I told myself, would simply drive me to an earlier death than was other wise in store for me. I was buried alive—but if I calmed myself, reserved my energy, there might yet be hope.

But would there be?... For I thought I saw now the answer to it all. The confidential government mission that I was to undertake next week.... I had not thought it would harmfully affect Boehler's interests, but now I could see that perhaps it would. And so he had wanted to be rid of me....

Yes, it all fitted in now.... His meeting us upon our arrival ... his mention of the tomb ... my introduction to Mahmoud, who must be one of his tools ... and last of all, his shoving me aside at the doorway, to be buried in the tomb.... His affability had been but a mask, this weird priest and the rest but a stage set.

In that case, then, there must have been some way arranged for Mahmoud to escape. There must be an exit through that door I could not find. Esther, at least, would not be buried alive as I was.

But what would they do to her, then, since they must leave me here... ? Good God! What awful fate was in store for her? Would they kill her mercifully? Or Mahmoud... I thought again of his dark eyes and now I saw there only lurking evil. I shuddered, groaned aloud.

And in the extremity of my agony, I realized that the answers did not fit. Some of these things might be true, but they did not explain all. They did not explain Esther's strangeness in these past few days, her remark at the meeting with Mahmoud. There were many things to which there was no answer.

What was that feeling that was coming over me, that made the flesh crawl along my spine? That there was—yes, that was it that there was something, someone else in the dark chamber. It was looking at me with ancient, long-dead eyes and I could not see it....

Yes, it was all true. It was as I had seen it. Esther had been taken back into the depths of the tomb by an ancient priest, was even now being buried, for all eternity....

I leapt up, screaming. I rushed to ward the vanished door, to batter my strength out in seeking it.

Ten feet away I stopped short. For I saw now what it was that had been looking at me, what it was that had seen me when all about me was only darkness.

There were two of them; they stood, one on either side of the spot whence Esther had vanished. They were black men, black as the night about them, yet I could see them plainly. They were

naked save for loin-cloths and queer, bird like headdresses. Each held a spear at his side.

They were two slaves of ancient Egypt, and they had come back from the long dead past to guard the entrance to Esther's burial vault!

And I had advanced too close to them. I backed away now, but too late. Already they were coming forward, spears upraised. Now their arms swooped downward, to drive the sharp weapons into my body. I felt the burn of steel in my shoulder.

I fainted then...

I CAME back to consciousness to find light once more about me. The stone at the outer entrance had been rolled back. Franz Boehler knelt above me, dashing cold water into my face.

The black slaves were gone. Later, when I looked, I found no mark of spears upon me.... Now an old man knelt be fore the space where they had been. He, like that first one, seemed to be a priest; he too was incredibly old and wrinkled; yet I knew somehow that he was of the present.

As he knelt he was speaking—in that ancient tongue I had heard before this day. I thought it to be an invocation to Thoth, perhaps, who kept the dead, to Thoth, the Hawk-faced One.

The old man finished speaking. Now he fumbled at the wall. And again a door swung open there!

Boehler raised me to my feet. "We'd best hurry," he said. "If she ever comes out of the trance and finds”

Already he was racing down the black passage ahead; but this time a flashlight in his hand cast welcome beams along the way. Close behind him ran the old man and myself.

"Damnably sorry about knocking you down," Boehler was getting out as we ran. “But I knew we'd never both make the door before it tumbled in. If you had gone, it might have been too late be fore you found out what to do. This old priest is my friend and I knew if any body could find the spring to open that door that I'd never known was there, he was the man. I thought—"

He broke off abruptly. We had entered another, deeper chamber—one built, perhaps, to hide the greatest treasures from those who robbed the tombs in ancient times. He flashed the light about.

In a golden niche, hewn out of the rock and beautifully decorated in colored paintings and hieroglyphics, a mummy-case was resting. In the case lay Esther! Her dark hair had fallen back, revealing her broad, white brow-weirdly white now. Her eyes were closed, her arms crossed on her breast. She had assumed the posture of an Egyptian in death!

Before her, prostrated in sorrowing reverence, forehead touching the ground, was Rachin Mahmoud. But of the ancient priest of Thoth who had led them here, there was no sign....

I started forward, my heart in my mouth; but Boehler stopped me. "A trance...." he whispered. "Dangerous to startle them...."

And while I waited, the old man walked slowly up to the golden niche. Before the two, he spoke a long time in the strange chanting tongue. He finished with a sharp word that seemed a command.

At the word, Mahmoud rose up, looked dazedly about him. Then Esther, too, arose from her resting-place. She looked around with frightened eyes, saw my anxious face. The fright changed to relief and a great happiness welled up within me.

"Peter!" she said in her old voice. "Where am I? I—I must have been sleeping—a long time...."

I took her in my arms.

Boehler mopped his brow. “Thank God," he said fervently. "And let's get out of here. This beastly place....I you know I think something they left in here centuries ago must have drugged the air. I've seen the damnedest things here more than once things that couldn't possibly be here...."

We hurried out of the tomb. I was carrying Esther, and when we went up the steps she tried to turn and look back. Some fearful premonition seized me; I forced her head quickly away. Mahmoud, dazedly bringing up the rear, turned and stared for a long time at the dark passageway. Then, shaking his head, he came forward and climbed into the car, his eyes burning with a strange dim light.

I was still trying to answer a thousand questions as we drove away. But there was little time for that. Beneath my hand Esther's brow was burning hot; her eyes were wild. She was not yet out of danger.

We drove swiftly home, stopping only to leave Mahmoud at his house. I got Esther into bed and called a doctor. Then, and then only, did Boehler and I find time for talk.

"I'm damnably sorry, old fellow," he said worriedly. "Terribly sorry. I never should have taken Esther out there especially after Mahmoud joined us. But the resemblance—it maddened me. I didn't realize there'd be any harm, I had to see Esther there, at the tomb. Then I'd know.... I'm sure she'll make out all right now...."

I had never seen him so genuinely troubled. I could not be angry with him. "I don't think you could have helped it," I said. "She must have known this was going to happen before we left England. Centuries before...." I broke off. "What sort of rot am I talking ?” I asked. And then I added: "You said you'd know then.

I wonder—now—how much we do know...."

Boehler's first words seemed irrelevant. "I found this tomb," he said, "just about thirty years ago. There was a mummy then in the outer chamber, whose face was like—like the one on the wall. I had the tomb locked and guarded—no one could possibly have entered. But a few months later the mummy and the case containing it vanished. We've just seen the case—but there was no mummy there...." He paused; his usually smiling lips were thinned. “Reincarnation," he muttered. "I don't believe that sort of thing...."

"Esther," I said, and I seemed to speak dully, "Esther was twenty-nine years old today...."

We both lapsed into silence....

FOR two days Esther burned with a fearful fever that I thought would sap all the strength from her frail body. She tossed about; she raved in that ancient language which I did not under stand. The doctors, frankly at their wits end, shook their heads and called the malady Egyptian fever, because they knew no other name.

By the afternoon of the third day they were ready to admit they could not save her. The fever was fast approaching its climax. It would burn her to death.

Thoth, the Hawk-faced One, I thought with a shudder of horror, will have her, after all. He will have her in his dark tomb in cloth wrappings.... I suppose the strain of those past three days had left me not quite sane.

Boehler, who had been constantly at my side, watching over Esther, now nodded his head. “There is one hope," he said. "Just one...." And he turned on his heels and went out.

A little later he came back. With him was the old priest who had opened the door of the burial chamber for us, seeming now even older than before.

The fever was now almost at its height. Esther was raving madly—raving in that ancient tongue. And while Boehler and I stood helplessly by, the old priest knelt beside her bed. From the folds of his gown he took a small vessel and from it dropped oil on Esther's forehead. Then he lighted an incense lamp. He anointed her nostrils, her eyelids, her mouth, the palms of her hands and feet.

He gazed at her intently for a moment. From his voluminous gown he now brought a roll of withered papyrus, a pen and ink. Then he spoke to Esther in the same tongue she was speaking, and she answered him. And the things she said he wrote down on the withered parchment.

He must have written for half an hour. When he was done Esther seemed to have quieted a bit, though the fever still burned and still she talked on. The old man rose, shaking his head sadly.

"What was done before must be done again,” he said as if to himself. “The prince looked back. It cannot be other wise...."

Without another word, he rolled up the papyrus and placed it back in the folds of his gown, then walked out of the room.

An hour later the climax was past. The fever was all but gone, and Esther breathed normally, sleeping deeply and quietly.

She awakened in a little while, and her first inquiry was for Rachin Mahmoud. In my worry I had forgotten that he too might be ill. I sent a servant to his home at once to ask after his health.

The servant came back to report that Rachin Mahmoud was dead. He had not been ill, Mahmoud's servant declared. That afternoon an old man had called to see him. Afterwards he had slept; and he had not awakened.

At the moment he died, Esther had be gun to recover....

NOT long after, I managed to effect a transfer to India. I thought it best, and anyhow, I did not love Egypt any more.

The change seems to have been good for Esther. You would think she had never lived through those weird days. She is gay and social. She dances, swims, plays golf and tennis with the young officers who are our friends. She is the life of our little British colony, and we are both very happy.

Yet sometimes I come upon her suddenly, alone. She will be sitting rigid, staring with her long dark eyes into nothingness, and for a moment she will not know that I am near.

I shudder then. For I know that Thoth is calling her—that now she is not my wife....

END