On The Knees Of The Gods

by J. Allan Dunn

Illustrated by Manuel Rey Isip

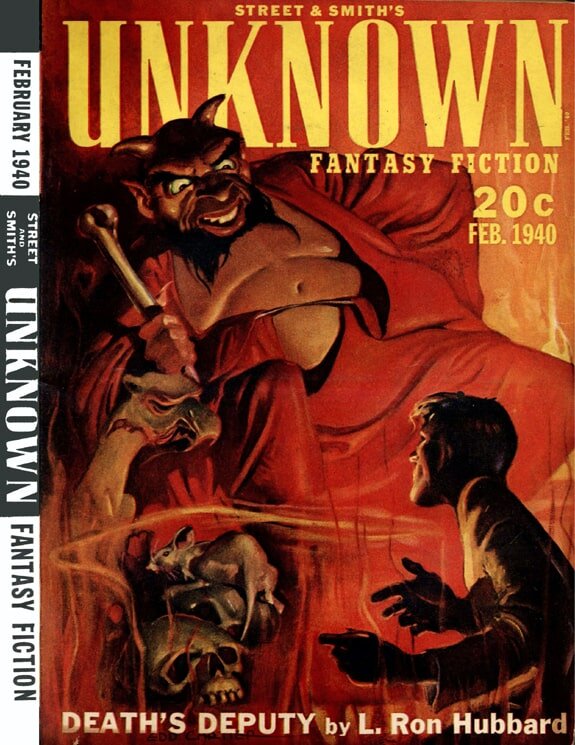

Originally published in Unknown, February 1940

Part 2

Read Part 1

V.

CHEIRON, chief of all the centaurs, reclined on a deep bed of oaten straw. There was a table in front of him that gave off odors of hot meat and other viands that flooded Peter's mouth with the flow of his salivaries.

Cheiron rose, forefeet first. He had a noble face, a long Greek nose that flowed into his fine brow, wide and lofty. It was furrowed with the lines of thought and of age. There were wrinkles about his eyes, lines from nose to mouth half hidden by gray mustachios and a sweeping beard, well tended, parted in two big curls. He was partly bald, but at the back his hair hung thickly to his shoulders.

His eyes were lustrous and they surveyed Peter with a glance that at once embraced and probed him. Wisdom sat on that forehead.

The fire in the entry was duplicated here. Its light threw dancing shadows everywhere. Cheiron's own shadow was huge upon the back wall of the cave. Peter's—if he had yet regained one—was blent with the others.

Stalactites hung from the vaulted ceiling, sparkling with silica. Stalagmites rose in pillars to meet them. The place had a strange beauty. Beside the table were stone seats and carved wooden ones. On the table a covered dish, ewers, bowls of fruit and one of oaten cakes.

"Be seated, Petros, you must be weary. You are most welcome."

The voice of Cheiron was like the vox human—a notes of an organ—deeply melodious. Beside those of Pvloetius they had great refinement. "First we will drink, then eat, and then you shall tell me your mission."

He poured a goblet of violet-hued wine, with a heady perfume, the taste of grapes and a still headier effect. Peter's grateful stomach glowed in comfort. The quality of the vintage stole through his veins. The stalactites seemed to sway a little like some vast swinging chandelier. Cheiron's benign visage showed like a genial sun in a dissolving mist.

Then things steadied, and Peter suddenly felt at his ease as Cheiron heaped a platter with hot meat. Cheiron told him it was kid, and Peter wondered if he had served kid to Pan.

Cheiron had a hearty appetite. His table manners were more efficient than elegant. There were knives, but he used his fingers, for the tender kid meat fell apart. There were savory spices in it, and gravy. Cheiron mopped oaten cakes in this, and gobbled. His fine nose took on color and now Peter saw broken veins in it, and in his cheeks.

When Cheiron ate, he ate, and he was no sluggard with the goblet. His beard got stained with wine and arded with fat and gravy. He would need grooming, Peter considered, but his hospitality seemed to swell with his belly, as he urged Peter to more and more. They topped off the meal with ripe figs and peaches. Peter was replete and fortified. No doubt the wine helped to make him bold.

It might loosen his tongue, he realized. He must not mention Pan. And it might be well to acknowledge himself a mortal.

"I am not a god, O Cheiron," he said. "But I am upon a task set me by Zeus. It was told me that, if I could gain the counsel of Cheiron, teacher of Heracles, of Jason and many young nobles, my task would be greatly lightened. Not that I am even noble, for we have none in my own land, where all are born equal."

“How long do they last that way, after they grow up," asked Cheiron shrewdly. “The idea is good but the wise—and the crafty-will ever rule the rest. What is this, my son?”

Peter produced the salve for sore frogs, explained its virtues. Cheiron accepted it, smelled it, set it down.

"It should be useful. It will take time to prove it. What may I do in exchange for this gift, and for the service you have rendered my people, whose feet are swift, but whose brains are sluggish?”

Peter had a swift and most unpleasant thought. He was glad that Cheiron did not possess Pan's ability to read his mind. Though the centaur was shrewd enough to guess

some of it. But not this time, Peter trusted.

Pan was a prankish god. He had taken a fancy to Peter, but just what did that mean? Suppose Pan had used Peter as a medium, through whom the goat god could get even with Cheiron?

Suppose the frog salve, instead of soothing, should turn out to be an irritant to those hoofs, that had been the crux of the misunderstanding between Pan and Cheiron.

It was too late now, Peter told himself. He could not ask for the salve back again, give any reason for it without bringing in Pan. And Pan, with whom Peter felt a real affinity, might be perfectly on the level with him. Mentally, Peter shrugged his shoulders.

This was just another matter on the knees of the gods, this time in the shaggy lap of Pan.

He was more inclined to trust Pan than Cheiron. Cheiron was no god. Part horse, part human. A freak of nature, a jest of the gods. But Peter. felt he could handle Cheiron. He could string him along. He was a good judge of his fellowmen. The old centaur seemed friendly enough, but he was not yet ready to grant favors too freely. The salve had yet to be tested. After all, it was not a great gift. He wanted to put Cheiron under an obligation that was worth while. To trade with him.

"Before I talk about myself," Peter said, "I've got an idea to set before you. I noticed that the feet of your people have been worn on the rocks, their beauty has been marred-especially in their battle with the Lapithae. Now if they were shod not—as I am—with leather, but with metal—"

He saw Cheiron getting the idea, stroking his beard and nodding.

“—such shoes would wear instead of their own horn. They need not be heavy." They could be renewed. easily when worn out. Your people would soon grow used to them. In a word-horseshoes!”

Peter had abandoned false ideas of modesty. If Cheiron wanted to think he had invented horseshoes, let him do so.

"But how would they be fastened?" asked the centaur. "If with thongs, they would soon chafe through.”

"I can show you. Give me paper or parchment, some sort of pencil.”

That is easy." Cheiron, reached back and drew from a natural niche. that served him as cupboard, some rolls of parchment. “Herein lies wisdom,” he said profoundly. “The wisdom of others from which I draw, and to which I add my own. Here is a blank sheet, here a stylus, with reeds and quills.”

THE STYLUS was a clip that held charcoal. Cheiron had a small pot. of glossy black ink, made from berries. Peter chose a split quill.. He was a fair draftsman and Cheiron watched him with growing interest as he sketched a horseshoe, marked the groove, the holes for nails, drawing also the shape of a nail, explaining it should be made of softer metal, not to split the hoof.

He explained further how a bar of metal -might be heated, shaped on an anvil. Cold-shoeing would do, he thought, since burning the natural horn might not appeal to the centaurs, at least at first. Peter had learned, once, how to shoe his own mount. He felt he could do a fair job of it now, if he had the shoes.

"They should, of course, be made of various sizes, kept on hand," he went on, as if he were perfecting details.

"It could be done,” Cheiron said slowly. It is a noble plan, one worthy of a god, Petros. But there is only one who could fashion these, if he were willing. That is Hephaestus, the. husband of Aphrodite.. Charis also is his consort.

“This idea would appeal to him. He is a wondrous craftsman and he is also a very crafty person, with plenty of devices with which to revenge himself upon those who make fun of his clumsy walk. The palaces and jewels of Olympus are his work.

He makes the thunder bolts for Zeus, his father. He made the net in which he snared Ares when he tried to make love to Aphrodite, and so turned the laugh upon Ares. Once he fashioned an iron throne for Hera, his own mother-and lo, she could not rise from it until he freed her.

"He delights to get the gods drunk on nectar. Once he gave some to me" Cheiron half closed his eyes, as if recalling some incident not displeasing. "He drinks deeply himself, and he has a terrible temper. He tempers metal but he may not control his own, or does not care to. A powerful being, Petros, but like that vagrant rascal, Pan, Hephaestus is mischievous. I bid you beware of Pan, Petros. Have naught to do with him. He respects none and nothing."

"I'll bear that in mind," Peter said gravely. He saw the trail he must follow branching off, in the way that the paths of the gods forked and doubled. They gave you a task to do, and never told you that it would prove twice or thrice as complicated as it seemed at first.

It was perfectly plain to Peter that Cheiron meant him to visit the testy and tricky Hephaestus. The centaur took it for granted.

"His smithy is in the heart of a burning mountain beyond the sea, Petros. “It is there you must seek him, surrounded by the man-eating, one-eyed Cyclopes, who are his helpers. I think he would make the shoes, Petros, if you once got to talk with him. You have the gift of speech, Petros. Above all, if you could think of something that would be a fitting gift for him."

IF? Another of those infernal IFS that kept cropping up like stumbling blocks. The man-eating, one-eyed Cyclopes did not sound so good. Odysseus, Peter remembered, had been made captive by one of them, Polyphemus, who meant to devour the adventurer and all his crew. Odysseus, a wily and resourceful chap, had bested Polyphemus by thrusting a burning pole into his solitary eye, while the giant was asleep.

There Odysseus had played in luck. Oh, well—

He finished his goblet of wine and Cheiron refilled it. He had guessed what Peter was thinking about.

“Your wits must pass you by the Cyclopes, Petros. They are hideous and strangely monstrous, cruel and bloody of nature, and horrific to behold with their frightful mouths, their hairy bodies and their huge eyes flaming in the center of their foreheads."

Peter wondered for a second, if Cheiron was getting a kick out of trying to scare him. Probably 'not; Cheiron wanted those shoes. The old boy was kindly enough. He might be cagey about Peter's proffered gifts, as others were warned to be of Greeks presenting them. And the learned Cheiron was beginning to show a more vulgar side. He loved his dignity and his wisdom, he was an egoist-as all gods seemed to be. And he was getting slowly, but surely drunk, though he was still shrewd, perhaps with wits sharpened in some ways by the liquor, with caution predominant. He belched in almost prideful complacency.

"About the task?" he said.

Peter decided not to tell all that he had been asked to do. He might well be allowed to appear more or less mysterious as a messenger of Zeus, even though appointed willy-nilly.

"I have to seek out Python," he said. "It is said he is in hiding because of Apollo, and Artemis, who seek his life.”

"I see. I see. Zeus sends you to Python. For what? Nay, do not tell me. To say little, listen much, and see widely, proclaims him who possesses wisdom. “But I may wonder. I have heard of a magic jewel, of a maiden held, perhaps as pledge against the fury of Artemis and her brother. I will make a bargain with you, Petros—”

He hiccuped on the word. He could hold his liquor better than Pan, Peter fancied, but he liked it.

"—persuade Hephaestus to make those shoes, Petros, and I will tell you how to find Python."

"How shall I reach Hephaestus, across the sea, O Cheiron?”

"Sleep, and the night, bring counsel, Petros." Cheiron yawned, finished his chalice. "In the morning I will tell you. Poseidon may help us. Is he not known as Hippios, did he not create the first horse? Is lie not our guardian tutelary? We shall see. · As for Hephaestus, you must call upon your own genius, Petros. One does favors for him, rather than ask them. There is one thing in your favor, if you win through to him. Your hair. It glows like the iron he takes from his fire and hammer's on his anvil. He is god of fire, even as Poseidon is god of water. And he may take your hair as a sign."

Peter ran a hand through his crisp thatch. It was inclined to be curly, and at school and college, he had inevitably been dubbed "Red" He hoped it would prove an asset.

Cheiron yawned again. "I am ready for sleep, Petros. There is fresh straw in a rock chamber near the entry. Spread it for yourself. Sleep well. Inspiration comes through the Gate of Horn, whispering to mortals who are locked in the embrace of Morpheus. I wish you well, Petros, for you have intrigued me with the idea of those horseshoes."

Cheiron, Peter mused, as he went to make up his bed, was more genial than generous. He did not believe in bestowing something for nothing, and the frog salve was not enough. Moreover, he put it up to the mortal to deliver.

PETER was prepared not to sleep, with the Cyclopes on his mind, and then Hephaestus. He might beguile the fire god, though he did not see how, but the one-eyed anthropophagi listened neither to rhyme nor reason. But he was tired, he had a full belly after hunger, and a skin pretty well filled with wine. He curled up in the straw and knew nothing more, sleeping dreamlessly until the sun shot a golden shaft fairly into the cave at dawn.

He had a slight hangover. Cheiron's wine was new and powerful. It was never given time to age, he supposed, and there was too much honey mixed with it, to sweeten it.

The acidity of his stomach craved fruit juices. He walked back to get some from the leavings on the table.

He wondered that Cheiron's snortlings had let him sleep at all. The centaur lay upon his side, six-limbed. His legs were stretched out in limber ease, one arm was his pillow and he was automatically scratching his ribs with one hand. In the soft light of dawn, for the sunlight did not reach the back of the cavern, he looked benignant but somewhat bawdy.

Peter took the fruit and went outside the cave to the ledge that fronted it, gazing over the wild landscape. He could not see Olympus from there, and he did not want to. He was fed up with Olympus, but he was not rash enough to make a third attempt at breaking through the in

visible mesh that had been cast about him, like a spell. The memory of the flaming bolt, the plutonic stench in his nostrils, the sight of the incinerated cedar, was too keen.

He saw nothing of the centaur troop. The vale below the ledge was empty.

The fruit helped, but the craving for a cigarette again attacked him, He leaned his aching head on his hands and thought he felt his parietal plates pulsing.

There came a hail from the valley. Two young centaurs had trotted into sight. They seemed to know all about him.

He saw their shadows-strewn wide on the turf, and thought of his own. It was coming back, barely visible now, just a mere film, barely to be distinguished, almost an. illusion. The ambrosial aura was wearing thin and mortality would prevail again.

"Does Cheiron wake?” asked one of the centaurs. Peter saw that they bore between them ewers, lengths of white cloth and an amphora that was stoppered, which he guessed held liquor for Cheiron's morning's-morning. He hoped the ewers held water, and that he could get the loan of a towel.

He was still filthy from the fight, sweat had dried into the grime of travel. He heard Cheiron rising, roused by the voice.

Peter decided he was a bit low, and that a snifter from the amphora might restore his morale.

Cheiron's voice came booming.

“Come up, Dolon! Come up Atocles! I will join thee, Petros, when I have made my toilet. Then you can lave.”

Cheiron's valets came trotting up, past Petros into the interior of the cave. Presently one of them came back, knelt, for all the world like a trick horse in a circus, Peter thought, and handed him a shalloy chalice filled with golden liquor.

"It is not nectar, O Petros. But perhaps it will serve. My name is Atocles."

The liquor served. It smelled like Napoleon brandy. It tasted like it. It coursed through his system with a tingling warmth that pepped Peter up amazingly. He felt tops. . ..

Dolon came with a basin and a towel. He produced an ivory tool with which Peter cleaned his nails, after he had washed up. There was no soap and Peter was a bit ashamed of the dirty towel, but he felt more presentable.

He stayed where he was until Cheiron appeared. The centaur's beard had been cleaned and curled; he was well groomed, faintly redolent of brandy.

“While the cave is being cleaned and breakfast provided, let us take a stroll, Petros," he said goodhumoredly. He led the way to a high peak above the cavern. The sun was behind them. Far to the westward stretched the Ionian sea looking like dark-blue, watered-silk faintly heaving.

"Those lies the forge of Hephaestus," said Cheiron.

There was no land in-sight. Peter knew that three hundred miles distant was the toe of Italy, the Straits of Messina between it and Sicily, where Mt. Etna nursed its eternal fires.

And there, in this realm, this dimension into which he had projected himself, Hephaestus lorded it over the Cyclopes-himself the father of one of them-sooty, sweaty monsters,-laboring night and day in his smithy, torn with cannibal appetites, rebellious against their forced labor, yet fearful of the fire god's anger.

SOMETHING HAD HAPPENED TO TIME!

It was as if some Supreme Hand shifted an hourglass, so that the grains that ran one way now flowed another. Peter was engulfed in some sort of cosmic maelstrom.

"I will have Pyloetius bear you to a place where you may meet Poseidon,” Cheiron said. "Also I will give you a scroll. I think that when he reads it he will arrange for you to reach Hephaestus. When you return with the horseshoes I will keep my promise. Now, let us return to the cave. You must be hungry."

VI.

THE TEMPLE OF POSEIDON was in a little vale that opened to the sea. It was too long a journey for the aging Cheiron to attempt, even if he considered the occasion one of sufficient importance for him to make the effort. .

Pyloetius and Peter took two days for the trip. Peter's shadow had been restored but Pyloetius made no comment. He might have thought Petros was disguising himself as a mortal-since a god might be able to project a shadow at will, where a mortal might not get rid of one.

Peter had Cheiron's scroll, and a young horse colt went with them, willingly enough, unconscious of its fate. It was intended as a sacrificial offering to the sea god. Peter thought the choice cruel, coming from Cheiron—himself half-horse, at least in body.

He saw the temple at dawn, a massive structure of Doric architecture. The sun flushed the great columns and the decorated podium with rose. The shadows were violet, the whole structure seemed ethereal despite its solidity.

The main building was reached by steps within wing-walls on either side the podium. There were no other worshipers as Peter, bearing the scroll, mounted, with Pyloetius going nimbly beside him.

· Peter gathered that, between Poseidon and Hephaestus, there might be a bond because Polyphemus, who had been outwitted and slain by Odysseus, was a son of Poseidon, and so allied to the Cyclopes who served the god of fire. The scroll set that forth, and introduced Peter—Petros—to Poseidon as a messenger of Zeus, who was a guest of Cheiron, presenting to Hephaestus an idea Cheiron hoped would be approved by him. The favor was to Cheiron, vouching for Petros, beseeching the ear of the Mighty Forger.

Peter wondered if the approach might be better on the distaff side, through Pan and Amphitrite. But Pan was absent.

Pyloetius thought that Poseidon would furnish transportation in the shape of a chariot drawn by dolphins, that would attend Peter while Hephaestus made the shoes. Cheiron had no doubt of the successful issue of the errand, and Peter tried to bolster himself with the centaur's faith. But he still did not enjoy the idea of the Cyclopes.

The colt was on a lead noosed about its lower jaw. The steps bothered and excited it. Halfway up, it left droppings and Pyloetius shook his head.

"It is an ill omen to foul the steps of the temple," he said solemnly. “But we may not go back, for our approach is noted."

As he spoke a gong clanged brazenly within the temple. Bronze gates slid apart automatically, with the muffled sound of rushing water. A deep 'voice chanted rather than spoke: !

“Who seeks the shrine of Poseidon?”

Pyloetius knelt on his forelegs. Peter made due obeisance as a sense of awe and mystery invaded him.! The colt whinnied.

"From Cheiron I come, escort to a messenger from Zeus, who bears a scroll setting forth his desire, bringing also a sacrifice.”

The temple was dimly lighted. Peter's shadow was not in evidence. In the rear of the vast building, whose ceiling was upheld by a double tier of columns, he saw a fire rise and fall upon an altar, viewed through a lattice of marble.

A temple attendant came and led away the colt. He motioned to Peter to come with him, held Pyloetius back with uplifted palm and a gesture of dismissal.

Peter followed. A second attendant appeared and showed him into a chamber behind the altar that, he saw as he passed it, was upheld by dolphins at the corners, with bulls and horses sculptured on its front.

THE CHAMBER was deserted. It held no furnishings save a great chair, or throne, cunningly fashioned in the shape of a fluted shell.

Peter was left alone. Time passed—he supposed time passed. There were things in this god-land hard to assimilate, to comprehend, like problems in high mathematics. And there were occasions that might be classed as ungodly. He was well into the web. What he had to do was to keep a stiff upper lip, not to cross bridges before he came to them, not to burn them too readily behind him.

Above everything, not to let fear weaken him.

There was no good worrying about anything in advance. There might - be nothing to worry about when it came to it, and if there were, worry would not do him any good.

But there, was something about this vast, silent, lonely chamber, with its empty throne, that was psychic --that broke down logic and reasoning. Peter fought off fear at arm's length. If a chap panicked he was sunk, no doubt of that.

The stone courses next to the high ceiling were broken by latticed transoms. Now the sound of chanting filtered through from the main fane.

"Eternal Mystery of Fate!

The vibrant silence trembles

And with awe, the craven hearts of men

Stand still 'twixt fear and hope.

Poseidon, Hear!"

A priest and his chorus—

"The mortals quake before the Unseen

Presence;

Poseidon, at whose brief nod, the desti

nies of men,

May sink in misery or, glorious, rise in

triumph.

Poseidon, Hear!"

Poseidon lorded it over his own domain pretty well, Peter thought. Zeus was the supreme Head of the Pantheon, but he probably did not interfere with the god of the sea.

The chant went on, rising and falling in rich cadence. Peter imagined it had a great effect on the suppliants for favor, fishermen, sailors, prone to superstition.

"By Will divine the shuttle weaves its

web;

By Will divine the shears their angles

close;

So mortals die as falls the severed

thread.

And, secret as the future of their days,

The moment of their lives so close at

hand.

Poseidon, Hear!

All Hail!

All Hail!"

It was an efficient ritual, compelling enough, but Peter ceased to listen. He felt some sort of psychic pressure. The chamber seemed being charged with something, a Presence, as yet invisible, holding him in keen regard.

Then he heard a soft sigh. The sweat trickled in his armpits as a greenish glow, nebulous, gradually assuming form, began to manifest itself, to assemble at the throne.

It was an eerie business. Ancient atavistic terror crawled upon him, ghost hairs lifted on his shoulders. It was the manifestation of the Unknown-Magic which is made up of ignorance.

A voice, soft and sweet and deep as the chime of a silver gong, murmured:

"Be not afraid, ye who seek a favor of Poseidon. He is not present, for he has gone to avenge insult upon the daughters of Erectheus, to rebuke the slight offered in naming the city of Athens after the presumptuous Pallas, rather than Poseidon. He would be in no gracious mood to grant thy plea. But I, Amphitrite, his consort and queen, am pleased to receive thee. Draw closer, thou whose locks are like a flame upon an altar. Speak freely."

Peter wished Pan had not run out on him. There was a disturbing quality about Amphitrite, an allure that was potently feminine, sirenic, of which his every instinct bade him beware.

PETER was in a jam, getting more involved every moment. He dared not offend the goddess, who might turn him into some sort of poor fish at will. He had to cajole her, this sea nymph who was the wife of Poseidon. She had a charm about her and a cajolery all her own, hard for a mere mortal to resist.

He was amusing her, for the moment, but he had a nasty feeling that her mood might not be constant—and if it were, might be hard to reciprocate with the proper balance of acquiescence and reserve.

She had bade him sit at her feet on the pedestal of the throne. His hair seemed to fascinate her. She ran her fingers through it, ruffling it, stroked his brow with lingering, tingling touch that at once soothed and stirred.

So might one stroke the fur of a new pet, Peter told himself. In self-defense, he went into the details of his mission, and now she commiserated him on the dangers ahead.

"Poor boy,” she said. “Forget this quest. Zeus may reward greatly, but he will not forgive failure. Do not forget how he slew Apollo's son, Phaethon with a blasting thunderbolt, when he failed to control the sun chariot. Already he has warned you. But I can place you where even Zeus may not reach you, in our golden palace under the sea. I will protect thee. When Poseidon returns, he shall place you beneath the aegis of his own power. I can do anything with Poseidon. And, while he is away, I am lonely, Petros.”

She had promised nothing about helping him to reach Hephaestus, only dwelling on the perils of the trip, the uncertain temper of the god, the horror of the Cyclopes.

"You will never return, Petros. Alas, that so bright and fiery a youth should be quenched too soon—"

Peter was confronted by the horns of a dilemma. If he admitted to Amphitrite that he was only a mortal whose human lungs could suffer no such sea change as a visit to Poseidon's palace under the waves, she would be liable to rise in wrath and majesty because he had deceived her, had permitted her to be familiar with him. He could imagine himself changed into a creeping crab. If he kept quiet about it—

She was divinely beautiful, there was no doubt about that. Her diaphanous costume enhanced the grace of her body. She gave out an aura that had something of the effect of ambrosia upon his senses--a sweet sea savor.

Her compelling eyes were green as the heart of a curving wave with the sun shining through. They hinted at dangerous, if delightful, depths. Peter thought of sirens, of how Odysseus had bound himself to the mast to resist their song, knowing that to give way meant destruction.

Her hair was the hue of purple-brown seaweed, softer than spun silk. It fell to her girdle, and beyond, making a veiled tent about herself and Peter.

It was not a fair deal, he told himself. The gods had their own especial weapons of glamour and enchantment.

The only one who could get him out of this situation was Pan, who was probably wooing his latest fancy, Pytis, the pine-tree dryad. Pan had boasted his ability to cope with Amphitrite, Pan had

Pan had said to think—and think —and THINK—when you desired anything badly. There was nothing Peter wanted more just now than the presence of Pan, as chaperon, or better still, to take Amphitrite off his hands.

He discarded all suggestion that Pan had deserted him, he summoned up his will—

Pan! Pan! Pan! Pan! Pan!

Peter was sending, a plea vibrating on the ether, praying that Pan would tune in. If he did not

The hand of Amphitrite crept about his neck:

PAN! PAN! PAN! PAN! PAN!

If Pan was his friend, if there were any affinity between them, he would hear-ånd surely, come ::

"You are distraught, Petros," said the goddess. Perhaps I do not ap; peal to you,”

Peter stalled nobly while this will emitted his message.

“Your beauty and your majesty are hard to sustain, O. Queen.”

There had been a subtle sharpness. in the quality of her voice. A bell. that chimed might also toll. : PAN! PAN! MIGHTY PAN! PETER CALLING, PAN!

There came a strain of music, a lilt of notes that issued like airy bubbles charged with music. They broke in magic melody-far away, but coming closer. To Peter it was like an angels' serenade.

"Oh, the days of the Kerry dancin',

Oh, the croon o' the piper's tune;

Oh, the sheen o' the bright eyes,

glancin'—“

Pan's tune. The tune of Syrinx.

Peter felt the hand of Amphitrite stray away.

He heard a throaty, amused chuckle.

PAN, by all the gods! Pan, leaning against the portal. A hoof clicked as he crossed his hairy legs, his yellow eyes bright with a lively malice that was not spiteful, but spiced with a satiric humor as he gazed at Amphitrite, breathed a flourish and put away the syrinx.

"I see you are being kind to my protege, O Queen of the Sea!” he said.

Peter got up from the pedestal. He felt, thankfully, that he was no longer desired:

"Your protege? He claims to come from Cheiron."

"To whom I sent him. Not being able at the time to accompany him hither."

Amphitrite broke into rippling daughter that sounded like the gentle break of waves upon a shell-strewn strand."

"Pan! You have been philandering. And some minx has fooled you. Do not deny it. I know you of old!" She broke again into rippling laughter.

For a moment Pan looked actually sheepish. He winked at Peter.

“You go along, kid. I will amuse the lady."

"Kid” seemed pretty modern for Pan, until Peter realized that it was a natural enough form of address for a goat god to a junior.

"Wait outside, Peter. I'll try and arrange what you came for."

Peter went, gladly. He heard the click of Pan's hoofs across the marble floor as he went down the passage, through the deserted cella to the front stoa.

He saw nothing of Pyloetius, and imagined him trotting back to report to Cheiron.

The hours passed, the shadows shifted on the columned porch. Peter saw many: worshipers come to the temple, bearing various offerings, most of them libations of some sort. He had eaten a good breakfast, but he was getting hungry again when Pan at length came out, looking smug.

"It is arranged, Peter," he said. "Amphitrite will appear to some master of a trading vessel seeking a boon at the Temple, who will bear thee to Sicily, and wait for your return-”

Peter thought there was a doubt in Pan's eyes as to that return, but he had spent the hours of waiting in making himself once more the captain of his soul, and he nodded: .. "I'll come back all right, Pan."

“Good kid. Amphitrite told me of your idea about the shoes. Hepheastus will approve of that. He will probably want the credit for it."

"That's OK with me. It was great of you to show up, Pan."

"I've been keeping you in mind, Peter. I found that Pitys had despaired of my coming. I have another in my eye who far outshines her. This one is named Echo. She is shy but desirable. She answers when I call but she is hard to find. Which makes it all the more interesting. Amphitrite seemed to have been practicing on you when I arrived. She likes to keep her hand in. A trifle difficult at times, like all nymphs. And now let us go to a shepherd I know. He makes good wine and he will feed you."

"I could use something to eat,” Peter said.

“The captain of the ship will seek us there, later. I would have taken you to visit with another friend, Midas, King of Phrygia, a rare judge of music. He judged me the victor when I completed with my syrinx against Apollo and his lute, and Apollo was so jealous that he turned poor Midas' ears into those of an ass, so that now he keeps to himself. But we'll have a nice time with Epenor. I shall give you another lap. of nectar, and an ambrosial rub, before you go.

"I would not mention Amphitrite to Hephaestus, Peter. It seems that there has been some sort of a leak whereby the sea entered the forge, and Hephaestus believes Poseidon did it on purpose. Amphitrite mentioned it to me, but I doubt if she would have done so to you. She had no idea of letting you go to Sicily, Peter. She meant to detain you for her own diversion. I provided that. I did not undeceive her about your divinity. Come, let us go and find—Epenor. It is not too far."

PETER retained only vague memories of the visit with Epenor. The food was good, as Pan had promised, but the wine was better. Peter knew that he suddenly found himself only hazily conscious of his surroundings.

It seemed to him that Pan piped, while goat-footed satyrs danced with maenads and bacchantes in a saturnalia that left him dizzy.”

The next thing he knew, he was lying on soft skins in the stern of a thirty-oared trading galley, that was being propelled both by the efforts of the rowers and the great square-sail of striped fabric that hung from a great yard, and was sheeted home far aft.

The fore-peak of the galley was raised from the waist of the vessel, and in it was stowed much of the cargo. Aft, below where Peter reclined drowsily, was a lazarette for the rest of the cargo. An awning had been stretched above Peter's head to shut off the sun.

There were no provisions for shelter of crew or passengers. In that clime it was not often necessary, though Peter knew that violent and sudden storms often ruffled the sea, that now seethed gently in running hollows blue as molten sapphire.

The rowers were stripped to the waist; brawny Ionians. Back of Peter was the helmsman and skipper-owner, a bearded Phrygian in a red cap, an open vest over his hairy chest, and wide pantaloons. There were gold rings in his ears. He had a hooked nose and crafty eyes, and Peter thought him an admirable model for the portrait of a pirate-if, indeed, he were not one.

It was evident that he regarded Peter with reverence. That might well be due to Amphitrite and to Pan, seeing that Peter was traveling under their protection, and that the skipper might expect to acquire good fortune for his providing Peter's passage.

Peter sneaked a look at himself, and shifted to where the sunshine fell in a splash between the two sections of his awning, swinging apart as the galley rose to the surge. The ambrosia was working. He cast no shadows. They considered him divine, and they, themselves, favored by his presence.

"I am Tiphys, and thy servant," said the captain. "Will my lord eat and drink?"

Peter would, and stayed his bunker with oaten cakes, wine and fruit. Later, Tiphys said, there would be a more substantial repast. Peter saw the cooking stone on which, in a ring of dirt, a fire was made and the cook functioned.

The skipper had little to say. He was a rude type and in awe of Peter and his red hair, that Peter caught him admiring. The wind was light but fair. The rowers chanted as they swung at the long oars. Peter got out his whistle and played to them.

In the afternoon the breeze died down, the sea lost its blue clarity and sparkle, and seemed to labor, dull-green under a gray sky. The birds that had been escorting them Hew off with petulant cries. There bad been no sight of land since they dropped the coast, from which they had sailed, below the horizon.

Now they seemed remote from the world. A light drizzle started, became heavier and lighter in turns until sundown, when it cleared and a golden sunset showed through purple bars in the west, beyond their unseen goal, Sicilia.

The cook arranged sticks and wood. The skipper left the helm to his mate and went into the waist with the intention of lighting the fire, laboring with flint and steel, but having trouble in starting it. The twigs were damp and only smoldered as Tiphys tried to blow them into flame.

Peter joined him. He brought out his pocket lighter, spun the friction wheel with a flip of thumb and forefinger, puffed softly on the braided fuse, and soon had fire licking and crackling amid the fuel.

It was no miracle. Peter had not purposely made any hocus-pocus out of it. The principle was the same they used. But to them his deft movements made it seem that he carried a living flame in the little cylinder of perforated metal, and it confirmed his godhood.

THERE WAS broiled meat, with it more wine and fruit and oaten cakes. Simple, satisfying fare. The sky was clear and the stars pricked through, the wind blew gently and the night was warm. Peter piped a little, very softly, and slept long. The rowers curled up on and about their thwarts, the big sail drew steadily.

The next morning there were dolphins somersaulting and caracoling, their sides blue and silver in the pulsing, flushing dawn. The men pointed them out to each other with grins of approval.

They were a visible sign of the patronage of Poseidon, or of Amphitrite, his wife. Only the patron seemed disturbed and puzzled. He scratched his curly head, wetted a finger and held it to catch the breeze, and found none. He tossed scraps over-side and watched their slow progress aft. He ran an anxious eye about the horizon. There was sight of neither sail nor bird. The rim of the sea was a circle, a ring of deep-purple. Clouds were piling up in an argosy southward.

Peter did not consider himself a sailor, but he was tolerably weather-wise and knew the working of a fore-and-aft rig. He fancied the square sail clumsy. It was too big to handle easily, it furled clumsily and the big yard was hard to shift and brace. The galley was slow to come about, little good at sailing close-hauled.

Now it hung flaccid, useless. He noted that the flotsam the captain tossed over to port, as they were headed in the sun-path, west, came against the side, and he fancied there was more than mere attraction to it. A glance to starboard confirmed the idea that a current was setting them north.

In the night he had twice seen the helmsman using a light by which to inspect a bowl, in which floated a. scrap of wood that bore in turn a short, thin needle that had been magnetized by a lodestone. It pointed crudely north and south. A twenty-five-cent compass was as much its superior as an electric bulb is to a sulfur match. It was a forcible reminder to Peter that he was off his own course, astray on the sea of time.

These sailors were the equivalent of what the folks of Maine called apple-orchard mariners. They seldom were far from land, unless blown. there. They made costal voyages, relying more upon oars than canvas, often guided by beacons. This trip across the Ionian Sea was quite an undertaking. It might be made in two days with great good fortune, it was more likely to take a week.

Africa was far, far to the south, to i the north lay the boot of Italy and the Adriatic. Behind them Greece, ahead Sicilia, or so it should lie.

"I do not understand it," said Tiphys, shaking his head. "I have never seen the current set this way before. It looks as if the evil daughter of Phorcys, the sea god, ever jealous of Poseidon's dominion, seeks to bear us to where she can reach from her rock and pluck us from the boat as we avoid the whirlpool of Charbydis. Scylla, I mean, the six-headed monstress. As she did with Odysseus. Six of his men did she seize and devour, one for each horrid mouth."

He looked appealingly at Peter, who shrugged his shoulders. “Poseidon is far away, busy at Athens," he told the skipper. "We must trust in Amphitrite."

They lowered the useless sail and took to their oars, trying to offset the current. The seas ran heavily in gray hills that curled in sullen, foamless crests. The water seemed to lack any aeration, to lose buoyancy. The sky lowered and took on a dull hue. It was like looking up into a leaden dome. Waves slapped against the prow at the port bow with steady insistency, to offset the efforts of the rowers and the helm.

AT NOON the leaden dome had become a mass of dirty vapors, scudding steadily above them. The visibility was reduced to less than a cable's length, so that they seemed the center of a hemisphere of which the jobbling water was the uneasy floor.

Now and then a wave flung a heavy mass inboard, sousing the oarsmen. Presently two of them were forced to bail almost continually as the galley labored, her timbers creaking. She went sluggishly to the lee of wind and tide, always encompassed by the limit of visibility. Outside that flying veil they heard thunder muttering but no lightning pierced through. It grew cold. The men began to look at Peter as if he were a Jonah. The skipper looked askance at him.

When they essayed a fire for the evening meal, a wave extinguished it three times and they gave up the attempt. Day gave place to night reluctantly, gradually, eerily.

Peter heard Tiphys cursing as he looked at the bowl he tried to hold steady in his hands, as he consulted his floating needle. It had become demagnetized. He rubbed it on his lodestone, his adamant of Arabia, and it did not respond. With an oath he flung the outfit into the sea.

The waves that rose out of the sloshing blackness reared with cold fires streaking their slopes, broke in blue and green flame. About the middle of the night the galley suddenly shivered from stem to stern, from gunwale to keel, as if she had struck a rock, and then went staggering on.

It was Peter's idea that Etna, somewhere there in the void, unseen, was cutting-up, and that its tremors caused a submarine temblor. But he was not going to communicate his notion. That would make it only too plain that the gods were angry and set to defeat his mission. Tiphys might go about, but to return, appeared as risky as to go ahead.

For his own part Peter was firmly set to see the whole thing through. Granted he was in Godland, enchanted, at least under the control of powers beyond his own, he could see no way out until his task was completed. He was not allowed to step out of whatever dimension he might be in, therefore, the only thing to do was to make the best of it.

Dawn was merely a slow shift from darkness to gray mist. The rowers had taken shifts through the night and they had no spirit in their work.

Tiphys was scowling, "half drunk with wine. He looked at Peter, as if trying to make up his mind to see if his curved knife would be of any avail against this passenger, vouched for by Pan and dedicated to his own care by Amphitrite.

Of course, he could not slay a god. And he would have to make accounting to the sea goddess who had-appeared to him and laid her commands upon him. The trouble was that Poseidon did not have such absolute dominion over the sea as Zeus did over Olympus, or Pluto Hades. And it seemed evident to Tiphys that Phorcys was opposed to this voyage. Or Triton, Poseidon's unruly son, might be in league against him. All Poseidon's children were rebellious.

He muttered about this, as if to himself, but plainly it was meant for Peter.

Peter was being thankful he was a good sailor. A seasick deity would be, to say the least, undignified.

"I am a messenger of Great Zeus himself, Tiphys," he: said with a calmness he congratulated himself for exhibiting. “Great Zeus will see us safely through.”

He supposed that Tiphys had two patron gods, Zeus for land - and Poseidon for sea. The skipper said nothing more but continued to mutter in his beard, too low for Peter to know what he said.

The long day wore through, windless, thunderous with seas that ran in liquid pyramids, that tossed them . here and there, ever ready to fling them in the troughs, broach and sink them. They ate cold victuals, drank much wine to offset the clamminess and chill. The relentless current rammed them ahead of it, or rather side-wise, as they wearily tried to counteract it.

The wind started to blow hard toward nightfall. The seas rose and pitched the open galley about like a chip in a millrace. They shipped water steadily and wrought desperately to keep the boat afloat.

AFTER HOURS of buffeting, that left them spent, the wind passed, brooming the scud away and showing the stars and a rising half-moon. The sea fire vanished and the waves surged black as jet.

Tiphys gave a cry, pointing. In the southwest there was a ruddy, throbbing glow, high up. The active crater on the shoulder of the volcano cast its lurid glare upon the steamy vapor that hung over it.

"Now, let Zeus save us! Man can do no more,” said Tiphys. “We are bound for the strait.”

That glow should have been on their starboard bow, in the northeast. And now the current no longer buffeted but bore them, swift and strong on either side, as if they rode in a flume.

The wearied, despondent men, sodden without by brine, within by wine, cast themselves down, resigned and exhausted. Tiphys hugged his knees, a squat by the taffrail, after he had lashed his helm.

The red sun rolled up from the sea on their port quarter as they sped. Now landfall was all too clear the heights of Sicilia, the loom of Italy.

Across the sea there came a faint, sweet chanting. Tiph?s shuddered. "The Siren Sisters," he said hoarsely. "We shall clear their shore, but we are doomed."

The bleak precipices of the fateful strait seemed to rush toward them while the galley: appeared to be towed by undersea creatures.

The roar of boiling waters sounded, deafening them. The gat looked as if it would close in upon them, in a smother of spray and foam.

They neared two streaming crags, no more, Peter thought; than fifty fathoms apart. From one there belched out an eddying whirlpool that threatened to suck them into its fatal eddy. There Charybdis was imprisoned by angry Zeus, spewing her hate, hoping to stay her passion with the bodies of drowned men, crunching their bones to pulp.

On the other dwelled Scylla, changed by jealous Amphitrite to a twelve-footed and six-headed monster, with yelping jaws and rows of gnashing, avid teeth. ' Amphitrite : must have deserted them or her powers were failing. She might even be avenging herself on the recreant Peter, who had fled from her charms.

Peter got to his feet, clinging to a back-stay, shouting to make himself heard.

“Zeus deserts only cowards," he roared. "To your oars, shoot through the strait! It is our only chance."

He jumped down among them, booting them, shaking them, inspiring them to a last effort.

"If you must die, die like men," he bellowed, and språng back to the helm. “Give me a hand with this," he cried to Tiphys.

Out of her cave came Scylla, horrendous, ravening incredible, looking like a gigantic spider, shapeless of body, hairy of legs, her six faces those of hags, each more revolting than the other, reaching out for them through the spume with her skinny arms..

Peter swung the tiller, heading for Charybdis. They had one chance—that the backwash would hold them off. They were caught on the lip of the funneling sea, borne along it, bound to be sucked into the vortex, unless--the gods were with them. A counter eddy swung them—

"Now row! Pull, as if the Furies clawed you, my hearties! Pull, damn your salty hides, pull!"

The helm bucked. The blades dug deep: If anybody caught a crab, the crabs would get what Scylla' left. Peter and Tiphys viced their grips until their knuckles showed white as chalk, as they set weight and muscle to the long tiller. For fearful moments they hung on the verge of the watery abyss-slowly they drew, away. away.

Scylla howled above the gale, a howl of rage as her dozen bloodshot orbs saw the galley slide in a foaming trough, while the rowers, seeing safety ahead, made the stout ashtocks bend like bows.

"Pull, you bullies, pull!” Peter leaned and moved to the stroke of the oars like the coxswain of a racing eight, hitting up the count-beat.

Through, and clear, they shot. The open sea läy, ahead with the blue Lipari Islands dotting it. The strait widened. The sun shone, painting rainbows on the mists, that swiftly shredded away. Sea and sky were blue again, the wind fair and free behind them as they hoisted sail, and sped along the northern coast of the great isle.

They had to circumnavigate it. They could not attempt the strait again. Hot beams cheered and warmed them. They hailed Peter as their deliverer.

“Truly thou art a messenger of Zeus," said Tiphys, hastening to unseal a wickered jug of wine, pouring a libation into the now friendly waters.

Peter took a good long swig at the wine. Truly, he thought, there were wheels within wheels in Godland. He only hoped he was amusing Zeus, keeping him well disposed toward him, whenever Zeus bothered to think about the plaything he had wound up, like a sidewalk toy on his lap, and set down to do his bidding.

Tipays had some cargo to deliver at Syracuse but he held straight on past Catania and landed Peter at Aetraete, right at the foot of Etna, so convinced was he that Peter had delivered them from destruction. He did not even notice, nor did his men, that Peter's shadow was returning.

Tiphys promised to be back within the week, to wait another one. "If," he said, "we do not run afoul of pirates.” The crew was well armed and lusty, and did not seem to fear that they would not be able to give a good account of themselves to human foes.

Pan had given Peter instructions as to his finding the way to the workshop of Hephaestus. There was one vast split, rent by the volcanic throes, its sides built up by laya flows. It forked toward its end. Peter was to take the right-hand fork, and enter a cavern where it closed.

If—there was ever an if—the Cyclopes did not discover him and devour him.

Pan had a twinkle in his yellow eyes when he spoke of the cannibal ogres. Peter imagined that Pan liked to get a rise out of him, but that he believed Peter would win out in the end.

“They are witless folk, Peter, thinking only of their bellies. They cannot see far on either side without turning their heads, and they are not swift in their movements. You must watch the wind, Peter, for they have a keen scent, especially for human flesh.

"As for Hephaestus, he has a jovial side. Zeus guard thee, Peter. I shall be watching for your return. I am making a brief visit with Amphitrite. Echo can wait. She is too elusive, that one, unless one is in the mood for playing hide and seek.”

It was a grim trip up the fire-scarred fissure, its sides jagged, blown out by gases, sometimes smooth where lava had spilled down the steep slopes. He walked over lava that was brown and porous, like taffy, looking not unlike enormous cables of pulled candy. It was brittle and the seeming ropes were hollow so that he had to be careful of breaking through. Other lava was in flinty waves of black volcanic glass. He plowed through fields of black ash-that turned up sulfur-yellow under foot.

Everywhere masses of obsidian protruded in weird shapes. There was no living thing of plant or animal life. There was no water and the rocks gave off heat that might have been sun-stored or radiant from internal fires.

Every little while the ground trembled, while deep rumblings came from the great mass of the volcano. No sun shone into the gorge. It was veiled by the pall of vapor that hung overhead, or sometimes puffed up, rolling in cauliflower-shaped masses. Steam hissed from fissures. It might well have been another entry to Hades.

He saw no sign of the Cyclopes, heard none. At last he reached the black mouth of the cavern that led into the interior, where Hephaestus had his smithy and used the fire of Etna in his prodigious labor.

It was a nasty place to enter, and Peter summoned up all his nerve. Zeus would not let him turn aside, therefore, he must go ahead. The idea of an eruption haunted him, but he held on. At first he used his flashlight and found there was a sort of trail that skirted deep abysses where, deep down, he glimpsed erratic flashes of light, that belched fierce heat up to the vaulting roof.

Then, as he advanced deeper into the bowels of the mountain, he passed lateral fissures from which came glares of red light. These he passed swiftly, sweating with the growing heat and nervous tension. Once he saw a cataract of molten rock pouring down into the pit that engulfed it. There were great roarings, blasts of heated air.

The place was a natural tunnel, a conduit through which lava must have flowed, leaving the solid rock, as the liquid stream of mineral passed on, eons ago.

The mighty tube became more solid and he had to use his flash again, sparingly, thankful that the triple batteries were almost new.

It made a sharp curve and suddenly he saw light ahead, heard a tumult of clanging, emerged upon a ledge that faded away to his right, and found himself looking down into a vast chamber where monster figures toiled about fires, pounding at glowing shapes of metal through writhing columns of steam.

It was so vast he barely glimpsed the high roof, the irregular sides.

Near the center a pillar of fire rushed upward, whistling as it spouted from the reservoir of natural gas.

THE CYCLOPES were at work, slaving at their tasks. Now and then he caught the fierce glitter of their solitary orbs as one and another lifted a brawny, glistening arm to wipe away the sweat that dripped from their foreheads, varnished all their huge figures, clad only in short aprons of leather.

At the least pause a harsh voice stormed at them and they swung their hammers, plied their pincers with renewed energy.

Peter did not see the owner of the voice at first. Then steam gusted away and he saw the fire god, limping about a forge where a Cyclopes blew gigantic bellows, while Hephaestus turned a twist of glowing metal cunningly where flame broke through the bed of coal.

For all his lameness, he was amazingly, agile. The Cyclopes were giants compared to him, and he was twice the build of Peter, naked except for a girdle of spotted skin below his bibbed apron of leather. His voice, resonant and masterful, had the power to pierce through all the clangor, the whistling whine of the column of ignited gas. It reached everywhere, penetrating as the voice of a speaker transmitted through loud-speakers.

It was a steady stream of invective, ever varying, before which the Cyclopes winced and cowered and smote while sparks flew like shooting-stars.

Hephaestus cursed the Cyclopes wielding the bellows with a-fertility of imagination and point that made Peter marvel at the biting wit that was worse than any lash.

In this pandemonium the slaving, shining figures were painted ruddy where the fires limned them, black in their sooty shadows.

Hephaestus drew the twist of heated metal, placed it in a forge and attacked it with fast, deft blows as he held it on an anvil with his pincers. It gave off sparks like a firework.

Suddenly he flung down his hammer, threw the fiery twist from his pincers at the Cyclopes, who now stood quietly by the bellows with folded arms. The blazing missile struck him on his chest and he howled like a stricken wolf. His fellows turned to look at him.

Hephaestus threw up his arms, dancing jerkily on his mismated legs, reviling them.

"Begone, you misbegotten dolts! Begone, all of you, before I plunge this rod into your short-sighted eyes."

He snatched a rod from the forge and brandished it by one handled end-the other end at white heat.

"Fools! Spoiling more than you make! Am I accursed that I must use such clumsy clods? Begone!"

He seemed to tower in stature above them, his voice boomed and held such godlike purpose that they cowered away like beaten curs, stumbling over each other, over their scattered work, dodging the fires and the flaring pillar of flame, huddling together, their single eyes filmed with shame and fear.

Hephaestus made uneven strides toward them and they bolted into the side of the place, as rabbits bolt into burrows at the foot of a high bank.

The fire god threw aside his rod and burst into laughter that was tossed back and forth in stentorian echoes of mirth.

His wrath had passed like a summer squall. He sat on his anvil and rocked himself, then stooped and hoisted a stone jug into the crook of his elbow, set its neck to his bearded lips.

This was as good a time as any, Peter told himself. Before the humor passed. The bellows-blower seemed to have been faulty, or at least he had been held in blame. The sight of their abject exit had made Hephaestus forget his spoiled metal.

But not all the Cyclopes had gone. As Peter made his way along the ledge that ramped down in zigzags to the floor of the mammoth sinithy, a gigantic figure stepped from a natural recess and blocked his path.