The Complete Llarn Cycle - Sword and Planet New Edition rePrint - 040

The Complete Llarn Cycle - Sword and Planet New Edition rePrint - 040

Read the Honest Book Reviews by clicking here!

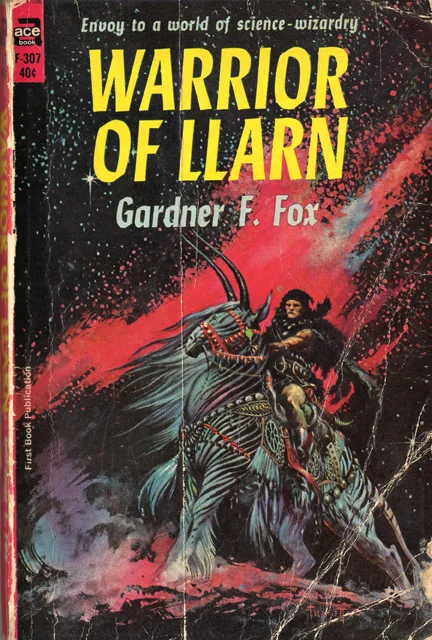

Originally printed in 1964 & 1966.

Accepting International orders.

Pages 286

Binding Perfect-bound Paperback

Interior Ink Black & white

Weight 0.42 lbs.

Dimensions (inches) 6 wide x 9 tall

This book has both Warrior of Llarn and Thief of Llarn. Both stories are complete. These books are Sword & Planet classics from Gardner Francis Fox. Originally published in 1964 and 1966, written as an homage to Edgar Rice Burrough's John Carter of Mars series. Gardner Francis Fox takes us to another world, where Alan Morgan, awakes on a planet countless distances from Earth. He has only his intelligence and his masterful swordplay to keep him alive. Llarn is a world of uncharted deserts where cities of incredible age lay broken and empty, destroyed long ago in the great War which had scourged the planet. Those few cities which remained, and those blue and golden-skinned people whose ancestors had lived through The War, gave a coldly hostile welcome to the strange newcomer.

Transcribed by Kurt Brugel & Richard Fisher - 2018

Read Chapter One below…

SAMPLE THE STORY BY READING CHAPTER ONE

Come to me, man of Earth! I call! I call!

The sweat was wet upon my body as I sat up in bed, eyes wide. I saw the wood panels of my hunting lodge bedroom, the silver of a moon-shaft tinting the quilted rug on the floor and the bureau drawer handles.

It is almost time. Soon, now. Soon. . . .

The clock on the bed table told me it was close to five o'clock. Nearly time to get out of bed, if I wanted to get that wolf. The air was cold and my breath made wisps of fog before my lips.

In my mind the echo of that alien voice still lingered. This was not the first time I had heard it, nor even the hundredth. It had come to me ever since I can remember, first as a small child, then as a youth and now—as a man. It was an old friend.

And yet—

It had been so long since it had called to me across the void and the eons, from whatever place in space and time it occupied. I had come close to forgetting all about it. I shivered and slid back under the heavy covers, not sleepy, just puzzled.

Soon now, it had said.

The time was come for—what?

What did the voice want of me? What mission was I to go on for this being whose mind was so incredibly powerful it could bypass the barriers of the space-time continuum to find and summon me? I lay there and tried to think, to go over what part the voice played in my life, its meaning and its inexorable hold on my body and my mind.

All my life I have heard the voice.

It was no more than a whisper in the dim recesses of my mind at first, while I was a small child. A purr of pleasure at being with me, at having—found me. In the years that followed its first appearance, the whisper became a part of my very being, as if it were a lonely animal discovering a friend. Never did it frighten me, not even in those early years when it came strongest between waking and sleeping. Never did the voice call me by name. Not once did it say Alan Morgan, nor did it acknowledge the life that occupied my waking hours. Having found me, it was content merely to be with me. Already the voice regarded me as its own; its property, in a manner of speaking. I was too young then, too filled with childish fantasies, to put up any opposition.

I say a voice, because I know no other way to describe what it was that touched my mind at such an early age. With maturity, I understood that the voice had never spoken to me, other than with flashes of its own thought processes. I sensed an emotion of satisfaction, of pleasure, and also the fact that after many failures, it had succeeded in some sort of quest.

I was the third and youngest son of a prosperous Middle West lawyer. There was nothing about me to suggest a reason why I should be singled out for—owning. I went to the right schools as I grew older, played the right sports; I even went two years to a military academy where I learned the use of firearms and became something of an expert with the foil, epee and saber, an ability I continued even after my college years, as some men continue with their squash or handball.

Somehow I sensed that the voice was studying me as I grew to manhood, as if it were a part of me in a sort of symbolic existence which set me apart—in my own eyes, at least—from the world about me. It became like a conscience inside me, forcing me to study, to exercise, to adopt certain mannerisms and habits which became ingrained in me as a way of life. Perhaps it guided me, through the use of its peculiar properties, along a path which it laid out for my feet to follow.

I did not fight it. I enjoyed everything I did at its subconscious bidding. I was a novice studying a role I was to play in later life, or so it seemed at the time. Though Earth is the planet of my birth, it held no allegiance from me as a human being. I felt that I belonged to another place and another time; I was here on Earth only because the laws of happenstance—a scientist might call it the theory of probability—had ordained it.

Such was the teaching of the voice.

And yet—

There were times when the voice went away and stayed far beyond my plane of existence for as long as a year, though rarely more than a few months. Once having found me, I was not to be let go, like a prodigal strayed and now, in a manner of speaking, on his way home.

I was filled, toward the last, with a sense of waiting. I was now a man, in my late twenties and in the full strength of mind and body toward which I had been guided, with a few hobbies, such as collecting old swords and learning their use, at which I excelled through natural ability, and with a flair for the outdoor life. I wanted no four walls around me, only the open woods or the salt spray of the ocean in my face.

I loved to hunt and fish, far more than any other member of my family, and we were all great sportsmen. In the weekends when I could get away from the law practice to which I had fallen heir by reason of my birth, together with my brothers, I fled into the woods. I must admit that I was never the lawyer my father and brothers were; to my mind the law seemed dull and uninteresting. I would far rather fight a twelve pound steel-head in the tidewaters of Big River or trail a bull moose through the Minnesota wilderness than sit through the most notorious murder trial.

In the wilds of the northern country, I could feel the voice more clearly inside me. The loneliness of the wind whispering between the pine branches, the crunch of pine needles underfoot, all were conducive to its coming.

I understood that someday the voice would summon me to it, to whatever world it called home, for a purpose which it had planned long, long ago, far back in time before my birth. It had hunted the star worlds for other men like myself, in ages past. I was merely its latest choice—to do what it thought must be done to . . .

My thoughts always became chaotic at this point. Either my mind could not grasp the thoughts poured into it or the voice-being never bothered to tell me what it was I must do for it. I was its servant—the latest in a long line—and it was desperately hoping that I would be the man who would achieve the goal it set me.

A little of my future it gave me, in my dreams.

It showed me unreal visions, glimpses of what was to come. I stood naked and alone on a great red desert in those dreams and ahead of me was a shimmering pinkness toward which I must run and run. Something in the pinkness was of the utmost importance to me and to the voice. Always I woke before I came to the pinkness, in a sweat of terror.

There were other scenes, too, from the mind of the voice being. I hovered in the air above a great metropolis that was old, old, though filled with men and women like myself, however differently garbed. I fled across ancient sea bottoms and dallied above the waves of an ocean that ran thinly and without force in these last years of its existence. I saw ruins of yet more cities, dead and pallid like old bones in the moonlight, and caught glimpses of men with blue skins.

These were not complete dreams but mere flashes of light and color, as though the voice-being called to me from far, far away and across a great gulf of emptiness. Yet each revelation was dear to me, held hungrily to my mind and heart because I knew that someday I would see the reality of what was only a dream at the moment.

I was hunting, as I say. The family owns a cabin in the Goose Island country, an expensive bit of redwood and plate glass, with all the modern conveniences. My father bought it as a retreat where he could study his appeal briefs and trial minutes; his sons had taken it over. For me especially, it had become a second home.

I loved its stained gun racks, the mounted deer heads and painted decoys on shelves in the big living room, its gray stone fireplaces a huge one in the living room, smaller versions in each of the five bedrooms—and the view of the woods from almost anywhere on the porch that borders the house on every side. This was a minor heaven in my eyes, for it was here, far from the crowded, hot city, that I received my most vivid dreams and heard most clearly the calling of the voice.

Of late, a big gray wolf had been terrorizing the houses in the valley below, raiding the chicken coops and runs, frightening the children, once even killing two of the town dogs in a running battle. My heart went out to the big lobo, for something in my nature responded to the wild, the unconquered; yet it had to be destroyed. This corner of Earth was grown too civilized to be long the prey of a timber wolf. And so I would have my sport and do the villagers a good turn at the same time.

I selected a Remington 721 for the job. It was a light weight gun and easy to maneuver in the brush if I had to snap off a shot in a hurry. I filled the leather pocket of my hunting jacket with brass-jackets and set out through the mists of early morning.

I had not yet eaten breakfast. I wanted no food smells about me as I slipped between the tree boles. Long ago I had come upon a narrow trail through these woods, too small to be made by a man or deer; I was willing to bet money that my lobo came by this path down into the valley and then back into the high hills. The cold frost was on the leaves and in my nostrils. I was vitally alive, so that my blood seemed to sing in my veins. I was promising myself a plentiful helping of flapjacks and sausages when—

I froze.

Alan Morgan! I cannot seize you! You are too—alive!

It was the voice. Troubled and frightened and desperate with urgency! I froze stock-still, to listen. And into that intense silence I heard the brush of fur against a low hanging twig, merely the bare whisper of a sound; yet my every sense was attuned to it.

Instinct makes a man perform acts without his consciousness being aware of them. The Remington was at my shoulder, the barrel steadying as my eye lined up gray fur against the vee sight. My finger squeezed. All this, even as I heard the voice crying out to me, almost wailing its despair.

The gun bucked. Flame ran from its muzzle.

The wolf leaped high, kicking. It was snarling and I knew that I had not given it its death wound. It flipped in midair and came down with all four paws scrambling at the ground. Then it was leaping for me.

Saliva dripped from red lips back drawn in a snarl, baring huge white fangs. Green eyes gloated on me as its prey. The hunter had become the hunted, all in an instant of human error. The wolf lifted upward at me, fore-paws outstretched, sharp fangs cleared for slashing. My gun went up. I struck with the darkly grained stock, felt the clamp of teeth on an arm and went down. . . .

I lay on my back under a huge, hot sun.

The rough grate of sand was under my naked skin, and as I rose to an elbow and stared around me, I knew a moment of utter terror. The woods and the wolf, the early morning frost and the Remington 21: where were they? Where was I, for that matter? I came to my feet, staring at my forearm. There were bloody streaks where fangs had entered my flesh, and blood welled up where the skin was torn.

I looked from my arm to the desert where I stood. It was vast, vast, stretching on for endless miles to where this world curved at its horizon. I turned in a complete circle. Nowhere was there anything but desert. And a big red sun, up above me, baking me and this sand as though I stood inside an oven.

It was not a disagreeable heat for it was dry and I was naked. Nothing remained of my hunting jacket, my heavy leather shoes, my canvas slacks, except the memory. Like the wolf and the Remington, my clothes were somewhere far behind me.

I stood and waited for the voice.

It did not come. It was if, by delivering me here to this desert, it had accomplished its purpose. The rest, apparently, was up to me.

I was still hungry. I remembered the flapjacks and sausages I had not eaten for breakfast and my mouth watered, reminding me that I was thirsty, as well. There was no place to eat or drink on these sands. I would have to go someplace else for that, quite obviously.

I began to walk.

As I strode along, I noticed that my body seemed to be stronger, my step lighter than it was on Earth, here on this strange new world. I had no way to account for this extra vitality at the moment. I accepted it as I accepted the fact that I was no longer on the planet of my birth.

This planet was somewhat smaller, I assumed, and its gravity less than that of Earth. My muscles, developed on the planet of my birth, gave me an added agility here. I remembered that the voice-being had told me it had brought others to this planet in the past; I wondered if they too, were from larger planets. Some of them may have been from smaller worlds, of course, in which case they would have had poor going in this red sand.

I walked until the soles of my feet were blistered and the pain in my bare feet was a red blaze before my eyes. I stumbled. I fell a number of times. The instinct for survival is a potent force in every man. It made me go on walking until I saw the pinkness.

Out of my dreams had come a memory. Yes, once I had stood here mentally as I stood now, physically. I had seen that distant pinkness. I knew there was an urgent importance about the pinkness. There was something inside it I must have. Without fail. The sight of the pinkness was a spur to my spirits. I tried to run, but the sand was too hot underfoot for that. All I could take was one slow step after another, trying to forget the pain.

I walked and walked. For miles? I have no way of knowing. The pinkness was always at the same distance. No nearer. No farther away. Time became a lifetime of red sand and hot sun and my own parched nakedness. After a long period the sun was not so warm. I turned my head and saw it sinking.

And faintly in the sky I saw—a mighty band of glistening matter. I came to a full halt, gazing upward. A ring around this planet? Could it be Saturn? But no. Saturn was a world filled with methane and ammonia gases, or so Earth science told me. The sky beyond the haze of atmosphere here was naked to the eye, not filled with drifting mists of poisonous gases. Besides, the air was sweet to the lungs.

I turned back toward the pinkness.

It was easier now, the walking. The sands were not quite so hot, nor did my feet pain me so much. It seemed to me also that the pinkness was drawing closer. My strength was returning with the coolness of dusk, so that I walked on with renewed confidence.

Dusk was gone and night was a bright silver radiance over this entire desert when I came at last to the pinkness. From that glittering band of matter that turned slowly about the planet came reflected sunlight in a shower of subdued brightness. The red desert sands looked dark, black. Ominous. They went everywhere except into the pinkness.

Inside the pinkness — was a shifting mist of rose and pale white and brightly shining silver that hid everything except glimpses of a black marble floor, highly polished, making a perfect circle perhaps two hundred feet in diameter. I came close to the edges of the flagging, finding a transparent wall before me shot with tiny red flames that gave to that wall a pinkish hue. The wall curved when it was twenty feet high, bending back upon itself to form a graceful dome.

I put my palms on the wall and pushed.

The transparent material was hard as glass. It did not yield. I walked around the wall, all around it, back to where I had started. There was no door to the thing, nor any window or other means of entrance I could see.

I tried to penetrate the shifting pink mists with my eyes, pressing my face as close as I could to the wall and straining my sight. I even hammered on the transparency for admittance, believing that the mists within it hid the source of the voice.

The voice!

Odd how it had abandoned me, once it had brought me to this world. As if its task were done, now that I had been delivered. The voice knew what this pinkness was. Long ago it had told me that the pink mists held something very valuable to the voice creature. I must get that prize set within the mists and—bring it to the voice-being.

I leaned against the wall. I came close to laughing with hysteria, from frustration. My eyes searched the sands. Hunting with ludicrous hope for a weapon, for a—a something to act as a lever and thrust me though the wall.

But how?

It was then I saw the blue men.

They were far away, about five of them, and mounted on some sort of four-legged beast like a horse. It was not quite a horse. I saw slender horns jutting from foreheads and hides streaked with dark bars but I was too far away to see details.

My back pressed against the wall.

The blue men wore fur kilts and capes, with broad leather belts about their middles each holding a long-sword and something like a revolver. Fur hats with upturned flaps gave them a barbaric appearance, and under the darkness of the fur across their chests I caught sight of a round medallion. Small white horns projected from the temples of the blue men, giving them an oddly beast-like appearance.

The foremost rider had seen me. His right arm went up and instantly the horned horse was a streak of barred lightning racing across the sands. It came with the speed and silence of the wind, barely rippling across the sands, and its rider was uncoiling a long rope as it ran, shaking out the noose.

The rope came fast for me, like a ghostly presence high above the desert sands. It settled down about my shoulders and it tightened, squeezing as if it were a living boa constrictor. I sought to turn, was yanked sideways off my feet. I fell to my knees, hampered by my arms pinned to my sides.

I dug in my feet, lurched sideways, backward.

The rider was yelling and laughing, coming for me, leaping from his mount—it was a horned horse with black streaks all over it, something like a big zebra—and gathering up the slack in the rope with infinitely deft hands. Up this close I saw he was very handsome, in a lean, saturnine manner, with faintly slanted eyes. His pale blue skin bulged with muscle.

He shouted something to the others, who laughed, reining in their mounts and watching with wide grins. They expected some sport, their faces told me. And I was the one to furnish it.

Again I rammed bare heels into the sand and lunged backward.

I felt the cold wall behind my shoulders. No help there. And then—

The coldness was spreading, enveloping me, gathering me into itself and letting me through to the pale pink mists that sang as I fell in among them onto the hard black marble floor. The rope was still about my shoulders. It had yanked my attacker off his feet, head first toward the wall as I fell, so unexpected had my action been to the blue man.

He rammed into the wall, which did not open to him.

He fell to the sand and lay still.