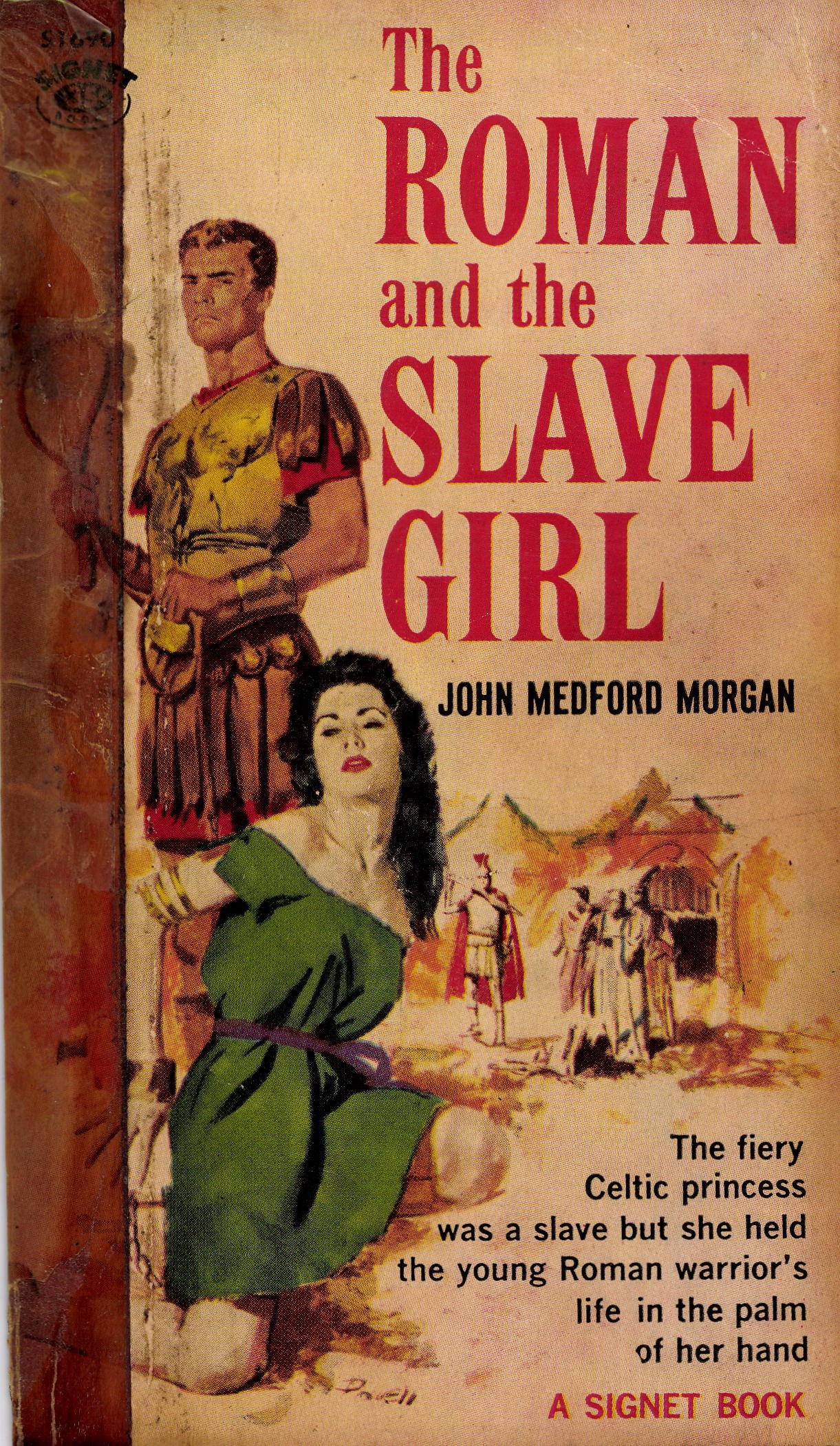

The Roman and the Slave Girl - Historical Fiction New Edition rePrint - 022

The Roman and the Slave Girl - Historical Fiction New Edition rePrint - 022

Genre: Historical Fiction / Vintage Sleaze

Originally printed in 1959.

Pages 144

Binding Perfect-bound Paperback

Interior Ink Black & white

Dimensions (inches) 6 wide x 9 tall

DEATH OR A CROWN

The fiery slave girl—

Freedom—

The golden wreath of empire—

Marcus could have all these if he but whispered “Kill Him” into the ear of the governor's wife.

And if he refused to help Cornelia in her plot to murder her husband, he would surely die ... a cruel and lingering death in the arena, torn apart by chariot horses or by any one of a thousand refined, barbaric tortures.

Death or a crown? The choice was his and he had to make it ... now.

Here is a robust and racy novel about ancient Britain where the wild pagan orgies were rivaled only by the barbaric slaughter ... where hotblooded warriors and wanton women fought each other to rule a rotting empire.

Transcribed by Kurt Brugel & Jason Duelge - 2018

Read Chapter One below…

LISTEN TO A SAMPLE CHAPTER

Audiobook format: MP3

Runtime: 00:26:38 minutes

Read by A. I. Stevens

SAMPLE THE STORY BY READING CHAPTER ONE

This was not the time nor the place for a man to die, with the blue sky overhead and a faint white touch of cloud moving low across its face, and the sun a pleasant warmth on a man's naked flesh. Over my body, which was stretched motionless on the stone altar and tied by rawhide thongs, the dagger in the hand of the chanting druid was a silver needle waiting to explore my entrails.

I had sought death before as a professional soldier, from the deserts of Parthia at the hands of rebellious tribesmen to the great Roman wall that straddles the isle of Britain. Never had it reached me, though my skin is scarred with the touchings of Visigoth arrows and Pictish swords. Now that Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos have wearied of spinning the threads of my destiny, I would die at the hand of a druid with a snowy beard blowing in the spring winds off the hills of Deva.

His dagger held my eyes in hypnotic attention. The reflection of an oak branch showed in its polished length. Oak trees are sacred to the druids, and in their groves they offer human sacrifice to Be'al, who is said by some to be the sun. My muscles were cramped by the rawhide thongs eating into them at wrists and biceps. My ankles were lashed to iron circles embedded in the stone. Once again I strained at them.

The bonds held firm. I loosened the muscles of my arms and legs, despairing.

Faintly in the distance I heard a shout, and the rattle of chariot wheels bouncing over stones. The druid heard those sounds, too, for now his voice increased in volume, and he slurred his words in his anxiety to finish this task he set himself. I saw his fingers freshen their grip on the dagger shaft.

Then the chariots were bouncing into view, two abreast. One of them was Celtic, with big wheels fitted with scythes at its hubs and ornamented with a single sunburst. The other was a white chariot with gilt paint on its grips and guard. A man drove the Celtic horses; a woman with hair the color, of Numidian jet reined in the two sleek bays that were harnessed to the gold-and-white chariot.

“Taeltain!” roared the man. “Taeltain, hold your steel!”

The druid sighed and looked down at me. In his eyes was the sorrow and regret of a man who knows his time is passing, that his gods have abandoned him and gone back to whatever place the old and forgotten gods still live. His beard and hair were white as the snows of Mount Ida, and his white woolen garment was girdled with a black rope from which hung the golden scythe and mistletoe cloth.

“A long time ago, it was the druids who gave the orders to the battle chiefs of Britain,” he whispered softly into the wind.

His dagger snicked into its enameled scabbard. He showed his back to me and waited for the man and woman to approach.

The man was a Celtic chief, clad in a fur pelisse over which lay a necklace of bear claws and a belt of metal coins from which a dagger hung suspended. His legs were encased in woolen trousers gartered in crosswise fashion to his knees. His brown hair was caught behind him so that it hung down his back in a club and would not blow in his eyes during a battle. A shield-man walked at his elbow.

I had seen his kind from the Isca as far north as the wall of Antoninus and beyond, into Pictland. There were more than a score of tribes in Britain in this year of Christ 410, and just as many petty chiefs.

The woman was another matter. She wore a white tunic cut in an alien pattern, and a red cloak bordered with gold. Her hair was sister to the raven, black with reddish tints in it, caught in a caul of gold threads that matched the frieze-work of her tunic. Her arms were bared to their elbows. On her right forearm she wore a spiral bracelet of red gold. She walked with an easy swing to her haunches, printing the lines of her slender legs against the linen of her gunna. Proud eyes, dark blue, raked my body without shame.

“Your men caught him on the Ratae road, journeying to Londinium, Caranac,” said the druid. “I was offering him as blood sacrifice to Be'al, to insure the success of your plans.”

Caranac came and stood over me, his right hand opening and closing almost convulsively. “Not my deed, this! I'd love nothing so much as to see you bloody your knife in his bowels, Taeltain. It's Edaine.”

“Your sister?”

“She was captured by Romans three nights ago, outside Glevum, during a raid. They took her to their river city, to be sold as a slave. I only learned of it a little while ago.”

Caranac glanced at the woman and saw how her eyes were lingering on my flesh. His face darkened and he rasped an oath.

The woman smiled faintly, as if aware that Caranac burned with fury. Her blues eyes lifted to my face. I saw amusement in them, and a little touch of curiosity, as well. I held her look for a long moment.

“I never saw a Roman before, Caranac,” she said sweetly.

“A Roman's built like a Celt or an Hibernian,” he rasped. “No better and no worse. Only sometimes I think they were made without hearts.”

“Heart or not, they have wide shoulders and strong legs, if this one's any indication. It would be a shame to kill him.”

Caranac grunted sourly. He said to the druid, “It's in my mind to offer him in exchange for Edaine.”

“The Romans would not let you get near, enough to the wall around Londinium to bargain with them.”

“Perhaps not, but the Roman can go in my stead. All he has to do is bring my sister to me, and he goes free.”

The druid snapped, “He goes free the moment he's out of your sight! You said yourself they have no hearts.”

“They do have honor, though, of a sort,” Caranac admitted grudgingly. “If he swore by Jupiter or by this Christus, who is a new god they've adopted, he'd do what he promised.” In halting Latin, he said, “Can you understand me, Roman?”

It had been ten years since I spoke his dialect, when I served in Britain under Flavius Stilicho, the Vandal general whom Honorius had murdered on the church steps in Ravenna. During those years I had learned other tongues. I could understand a little of the guttural jargon of the Visigoths, for I had fought behind the legion standards against Alaric, and some Pictish.

The words came easily enough. My boyhood had been spent at Camulodunum, along the Saxon shores where my father was comes, or count. I said, “I thank you for your kind thoughts, Caranac. My word on it: I will find your sister in Londinium and bring her safely to you.”

The woman flushed on discovering I understood her speech, but she did not lower her eyes. “I did not know the Romans bothered to understand the people they try to conquer.”

“How else can we talk to pretty girls who come riding through the forests in gold chariots?” And I grinned.

She laughed. “I'm well answered, Roman! Well, Caranac? Have you decided to take him to Londinium? If you have, give him back his armor and his sword.”

Caranac glowered at her. “I'd do it if only to keep the eyes in your head. Have you no shame, woman?”

She shrugged and turned away, and Caranac came with his dagger and cut the rawhide thongs which held my wrists and ankles. He loaned me a hand tug to sit upright, and tossed my under-tunic to me. I sat with the linen across my loins, chafing the blood through the channels in my wrists.

A tribesman came running with my cuirass and metal-tipped lappets. He dumped them at my feet as another ran up with my campagi, the leather service sandals, reaching to the knee, fitted with the fur muzzle and paws of a fox, and small silver chains. I pulled on my under-tunic and leather jerkin, fitting my cuirass on over it. Slipping my feet into the campaign sandals, I hooked the cuirass and kilt lappets into place. Over this I fitted my cincus, or sword belt, from which hung the scabbard for, my spatha, the long sword of the Roman officer.

Caranac held the blade in his bare hands.

“Before I give you back your spatha I want your vow, Roman.”

“By whatever god you name,” I told him.

His eyes were sly. “Which one do you worship most?”

I shrugged. “The Roman Empire became Christian under Theodosius. My mother was a Christian. My father offered gifts to Mars.”

I had to swear by the Cross, and by the sacred serpent of the war god before Caranac held out my sword. “I bring back Edaine or come alone, myself,” I told him. “But you must give me time. She may belong to a master who will not sell, at first. Or she may be still unsold in the slave mart by the old temple to Cybele. In that case, I'll be back within the week.”

The Iceni chief nodded and turned on a heel. As he walked toward his chariot, he said, “There's no time to get you to Londinium before dark. We'll make camp here and get an early start.”

His men came swinging from the forest with cooking pots and armfuls of dry underbrush. In a few moments a score of fires glittered in the clearing. The smells of roasting meat swept upwind. These Britons–call them Iceni or Brigantes or Cornovii–ate lamb and a kind of barley cake for the main staples of their diet.

The woman with the black hair and the dark blue eyes did not mix with Caranac and his tribesmen. There were a dozen of her own kind with her, big fellows clad in red kilts with gold threadings and white tunics, their leggings cross-gartered. Each man was swathed in a green cloak with red pendants and silver brooches. Long swords hung at their side from leather belts ornamented with silver and enamel bosses. There was a richness of apparel about them the Celts did not match.

She stood a little apart from her men as they laid a fire and brought a big iron pot filled with meat and water, and cut vegetables. My eyes discovered that her body beneath the simple white tunic was full and firm. Her own cloak, of fine wool dyed purple, was set with a great brooch of solid gold. When she turned and beckoned me, I went eagerly, for I wanted to know more about these men from the little island that lay west of Britain.

“Sup with me, Roman,” she invited.

There was mockery in her bold eyes, and amusement, and something I could not read, though I looked into her eyes like a sallow school child at his first love. It may have been pride or curiosity, or hard calculation, the kind I had seen slave traders use in the stone marts in Rome and Londinium when they haggled over their living wares. Her gaze ran over me. I stood a little straighter.

She spoke again. “Or does a Roman think himself too fine a man to sully his honor by eating with a barbarian?”

I laughed and put a hand on her arm, turning her so that she must walk with me to a flat rock by the rim of the clearing. Her flesh was smooth and warm beneath my fingers, and there was no withdrawal from my touch.

“Tell me your name and a little about yourself,” I asked.

“Deirdre is my name. I am daughter to Niall Noigiallach, the man you call Niall of the Nine Hostages, who has been dead now for six long years. Dathi is my brother, and high king in all Eire land.”

The pattern was becoming clear. A princess of Hibernia and a Celtic chief named Caranac: a bodiless mating of two cultures, aimed at driving out the Romans. That was why she was in Britain, perhaps, to succeed with statecraft where her father failed with swordplay. Niall had come raiding in Britain, and again on the Continent itself, with his chariot charges and his howling swordsmen and craisech men. He failed because he offered only death. His daughter was offering allegiance, and a better way of life.

Rome knew little of Eire land in this early part of the fifth century. It was a land that worshiped strange gods, through the druids. Its ard-righ, or high kings, ruled at Tara. Every so often, men came off its island shores in coracles and hide bum-boats to descend like an ancient locust plague on the civilized towns of Durnovaria and Glevum.

“Is that why you're here, to teach Caranac the value of unity with the tribes around him?”

Her laughter was the bright sound of water purling over brook-stones “You are not stupid, Roman. Is that why your eagle standards have conquered all the world but Eire land? Why, yes, since you ask: I'll tell you. What harm can the news do? Dathi sent me, with some of my father's veterans, to teach the Iceni and the Coritani and the Ordovices the good that can come from a single command. There are fighting men hidden all over this land, but they serve a thousand masters. Give them one, and—by the great Feis!—they'll push your people into the sea.”

The plan was a good one. We Romans always divided and conquered, using different gods or different puppet rulers to seduce the people from this allegiance or that, and put them at loggerheads with one another. Then we absorbed them, made them as Roman as ourselves, so that they wore our clothes and worshiped our gods, traded for Egyptian corn and Greek statuary, earthenware from Massilia and silk yarn from China. There were no Greeks and Gauls, Britons or Africans in the empire. Every man was a Roman, be he Syrian or Celt by birth. In this way, the empire was a unit and not a heterogeneous mass of conquered peoples. At the same time, it was this loss of individuality that the free tribes on the rim of our world resented.

Then, as her men came with wooden planks heaped high with sliced meat and crude wooden bowls heavy with thick stew, she talked of her homeland and the death of her father.

We sat alone, at some little distance from the blaze where her men were talking and laughing among themselves, or polishing their long swords and the bright points of their heavy spears. Her shoulder was warm against my own, and there was a natural fragrance to her flesh and her thick hair.

My arm hooked her yielding waist. At its touch she tried to draw away, as a wild fawn might start at a sudden sound. In the moonlight, her mouth was heavy and seemed swollen.

She fought me silently. She read my intention clearly enough. Under my palm, through the silken tunic she wore, I could feel the smooth skin of her side, and the touch put a ferment in my blood. Service at the wall had left me as celibate as a priest. For the first time in more than two years, I held a woman in my arms.

She hissed at me. “You Roman fool! One word from me and my men will skewer you on their spear points!”

“Caranac will not let them, Deirdre! I've become very valuable to him—alive!”

I held her tight to me, and shamelessly used my muscles to beat down her resistance and bring that soft body close against my own. With a hand twisted in thick black hair, I held her head motionless and kissed her, long and hungrily.

Her mouth was soft and moist, and it cradled my lips with an insistent hunger, as if the churning blood in her veins were betraying the cold distaste of her mind. And just as if that same warm blood were forcing her, she crumpled soft against me. There was a whimper deep in her throat. Lie as she would with her tongue, her own body revealed that she wanted me as desperately as I wanted her.

Though I freed her mouth, I still held her a prisoner across my thighs, enjoying her weight and softness. Her eyes blazed up at me. If she had been free to do so, the skean at her hip would have buried itself in my chest.

“I should not have done that,” I told her soberly. “Because now you've put a fire in me that only your own flesh can put out. And I can never have you, except by force, and that is one way I'd never take you.”

She hissed again, muscles contorting as she fought to free herself.

I went on, “I'm a Roman, and you're a princess of Eire, and the two don't mix. But I'll never forget you, and Venus is whispering in my ear that you won't forget me, either.”

Slowly, I relaxed the pressure of my arms and hands, and she slid sideways to find the flat stone with her thighs and crouch there, her eyes roving to the fires where her men sat unmoving. Both white hands were clenched into fists on her knees.

“Before now, Roman, I worked for Dathi to join the British tribes out of love for my brother. Now I do it out of hate for you and your kind! When we smash your wall around Londinium, all I'll ask for my prize is your living body. I'll take a week to kill you, for that kiss!”

“You'd be the fool you name me, then,” I said wryly. “There's hot blood in your veins that's better made for living than for thoughts of death. Even my death. You're not angry with me, but with yourself. You liked what I did to you. Someday I'll do it again.”

Her hand came up to claw at my cheek in wild fury, but she hesitated. Dathi had picked a good ambassadress in his sister. She would not jeopardize her friendship with Caranac for revenge on me. She would wait, confident that the future would deliver me into her hands.

Deirdre stood and gathered her red cloak about her.

“Remember my words when you lie helpless before me, Roman. Remember, when you beg for mercy, that Deirdre Ui Niall is no Roman harlot eager for your touch!”

She stalked toward the fires, proud and warm and furious, and Venus put the thought in my mind that the paths of this woman and mine were joined in a manner that only time could disentangle. Would it be by the arts of the torturer, or by the arts that Ovid, centuries before, had explained so masterfully?

I wrapped myself in my cloak and stretched full length on the ground. Sleep came swiftly, and with it, dreams of Deirdre Ui Niall.

The glory of Rome is dying and the dark ages are creeping in around us, for there is nothing that a man can do to hold back the future. It is a futile and a terrifying feeling to know that when a man has lived out his years there is no returning to undo what has been done.

As Rome dies, so the pagan gods die with her. Venus is no more, nor Mars, nor Juno, sister of Hecate and Isis. The Christus on the Cross is victor! That is good, for neither Jupiter nor Zeus nor Amen-Ra could hope to win against the barbarian hordes that are closing in around Rome on the Tiber and on Londinium on the Thames. There was no love in them: they were gods of bodily pleasure and of hate, of vengeance and of anger. The Christus is a god of love and forgiveness, and only through these traits can man hope to find that which has been lost.

Huns and Visigoths against Rome! Saxons and Jutes against Londinium!

Hairy men, half naked in their furs, with round hide shields and long swords, and a lust to slay and loot and rape that which they envy in their hearts for a lack of understanding: these are the midwives of the coming desolation. They will bring hot fire and cold iron to smash and trample learning and goodness and hope for the future

Will the Christus win them over?

Patrick says He will, and Patrick is a very learned man. He is a good man, too. There will be barbarians on earth until the second coming of the Lord, he has told me. Can this be true?

For once, I would like to read the future, tear down the veil of time, and see what may be written for this race of men. Perhaps if I could do that, I would feel a little better about the past and the part I played in it.

It was only a little part I played, on an island in a far corner of the empire that was Rome. Sometimes those close to me say I magnify my faults. I did what I thought best at the time, and who can ask more of a man than that? Still, when night closes in around me and I cannot sleep, I stare across the sea toward Britain and I tell myself that it lay in the two hands that I clench in anguish, to keep one little part of Rome alive for the days ahead. That one part, like a phoenix from the fire, might have been enough to carry light and peace to the rest of mankind.

Marcus Aurelius Valerian, have you let your loves and your hates topple all the world?

Morning found Caranac standing over me amid the cold dawn mists swirling upward from the mead. Those wisps of fog brought a heaviness of limb. Before Deirdre and I played out our little game, my honor demanded that I play another sort of game for this Celtic chief.

“We'll be close to Londinium by midday, Roman. If you fail me, or play me false, I'll hunt you down though it costs me my kingship!”

My eyes sought Deirdre, but could not find her.

“I won't trick you, Caranac. I've given my word.”

This soothed the wildness in his face, so that he attempted a semblance of calmness. “Edaine is my twin. We are closer than most brothers and sisters. It's my hope to wed her to her advantage.”

To her advantage and his own, I thought: perhaps to Dathi, while he bedded Deirdre Ui Niall. At that thought a kind of madness settled in me and I turned aside and walked toward the cooking fires, ignoring him, not trusting myself to speak as I should. I felt his eyes glowering after me, and knew the hate that was mirrored in them.

Within the hour, we were moving southward, past Icknield Way and Verulamium toward the London wall.

I rode beside the Irish woman, clinging to the curving hand-grip of her gold and white chariot, trying to ride it with as easy a grace as she did herself: swaying gently to its lift and fall, the reins in her hands and her long black hair blowing free behind her.

There were no words on her lips for me, but only a haughty look from those dark eyes and an occasional shrug of a cloaked shoulder. Caranac had brought me to her where she ate, and asked that she let me go in her chariot. The others were filled with fighting men, and only Deirdre traveled alone.

She saw at once that I was no charioteer. It delighted her to choose the roughest going, taking the wheels over stones and clumps of heath grass, skimming between forest trees and branches at the gallop. Her matched bays never seemed to tire of the game, and only tossed their heads high and pounded harder at the ground with their powerful legs. More than once I was almost shaken free of the floorboards and dropped under the wheels of the following chariots.

When we reined in, five miles from Londinium and close by the stone road to Sulloniacae, for the noon meal, she laughed derisively. “Stay on the ground, Roman. It's a safer place for your feet.” Then she was pushing past me, throwing a fold of her scarlet cloak against my face.

Caranac fed me hot beef and hot black bread, cooked on a stone at the edge of a shielded fire. He stood with Deirdre and watched me eat, and there was a feral hunger in his black eyes as his hands rested on the hilt of his long sword, the scabbard tip of which was dug into the ground between his feet.

“I can't put the thought from my mind that you'll be my sister's death, Roman, once I set you free,” he told me.

“Then kill him, here and now,” said Deirdre, smiling wickedly.

Caranac glanced at her with some surprise, for yesterday she had been telling him to clothe me and return my sword. He said as much, then added, “I don't know whether to be glad or angry at this change of heart. You sound like a scorned woman, and—”

“Oh, by Crom Cruach's brazen face!” she swore. “You veer from one fit of rage to the next. You scowl and you leer in answer to whatever evil thought possesses your brain for the moment! Smile for a change, and hide the blood lust in your heart.”

Caranac reddened and looked uncomfortable. I thought he had tasted her sharp tongue before. I wondered if he'd dared to kiss her. All this time I ate on, for there was a good walk before me until I came to the wall, and the chariot ride that morning had sharpened my belly for something more substantial than words.

Caranac stared from one of us to the other, and his scowl grew blacker the more he saw. Then he said, “Enough talk. It's time to be away from here, Deirdre, before a Roman patrol sights us and gives the alarm. You'll find the road to Londinium beyond the trees to the west, Roman.”

I wiped my hands on the edge of my cape. “I know where I am, Caranac. Tell me only where I am to meet you, when I bring you Edaine.”

“Do you know the Roman burial ground near the road to Camulodunum? There are some huts nearby, belonging to the marshland charcoal burners. I will keep a man at those huts, from this day on. Give Edaine to him. He will find me.”

He swung on a heel and walked away.

Deirdre continued to look at me. “When you go back to Londinium after bringing him his sister, take a ship for Rome, if you want to live. Because the tribes will be overrunning your walled city in a little while. If you're alive when I drive my chariot across your Forum, you'll die an unpleasant death.”

She lifted her dagger half out of its sheath and drove it back with a sharp metallic sound. It was as if she drove its length into my flesh. Then she whirled and strode away, her cloak swinging out behind her in a flood of scarlet, her black hair like the fur of an animal decorating it.

The wind came off the clay hills and stirred against my face. I had life, and a promise of death. Londinium lay five miles away, and in Londinium was Edaine, the Iceni woman.